Hello, this is Jooyoung Kim, engineer and music producer.

Today, I want to talk about panning, which controls the left and right placement of instruments. To explain panning, let’s first discuss how to create a stereo image.

- Creating a Stereo Image

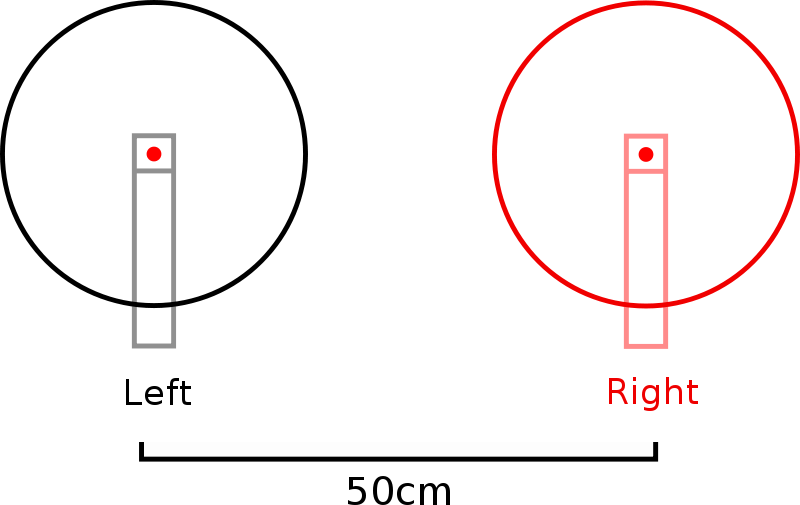

Stereo imaging starts with microphone recording techniques. On the left, we have AB stereo miking, and on the right, we have XY stereo miking.

AB stereo miking forms a stereo image by utilizing the time difference between sounds arriving from the left and right. In contrast, XY stereo miking relies on the volume difference between sounds arriving from the left and right.

Inspired by this, panning moves the audio source left and right by manipulating volume differences, much like the XY stereo miking method.

A question may arise: How do we create these volume differences to achieve panning? This is defined by the Pan Law.

- Pan Law

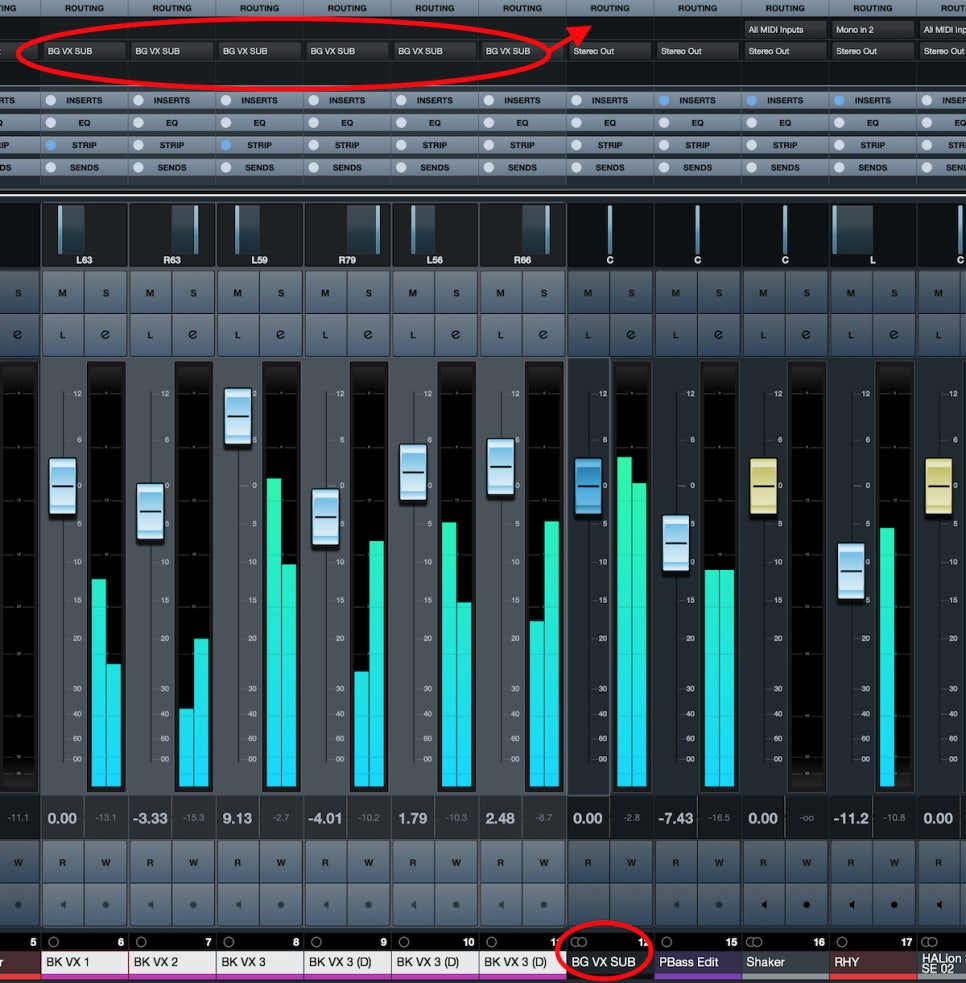

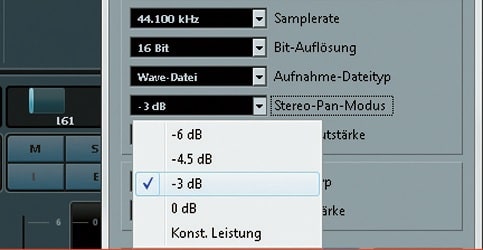

Pan Law settings in DAWs typically include 0dB, -3dB, -4.5dB, and -6dB.

The reason for these settings is that if you move an instrument to the left or right by simply lowering the volume of one side, the overall volume decreases as the instrument moves. This scenario occurs when the Pan Law is set to 0dB.

In the case of -3dB, the center volume is reduced by 3dB, ensuring the volume remains consistent when moving stereo sources left or right.

For -4.5dB and -6dB, the center volume is reduced by the respective amounts, making the sound appear louder as it is panned left or right.

This might sound complicated, but there’s no need to overthink it. Just be aware that there are various panning settings.

In practice, adjusting the volume balance while panning is common, so you don’t need to worry too much about it.

- Haas Effect

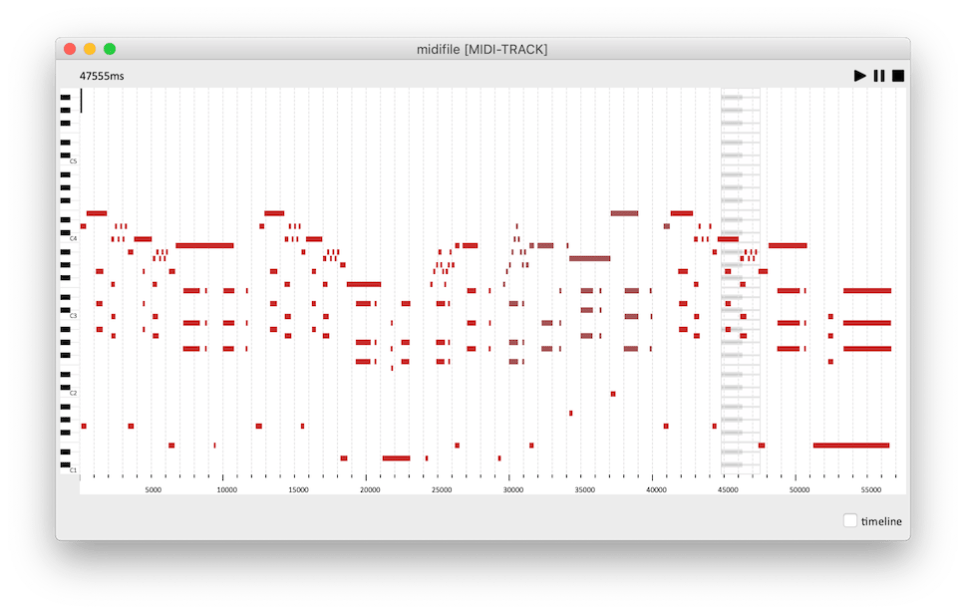

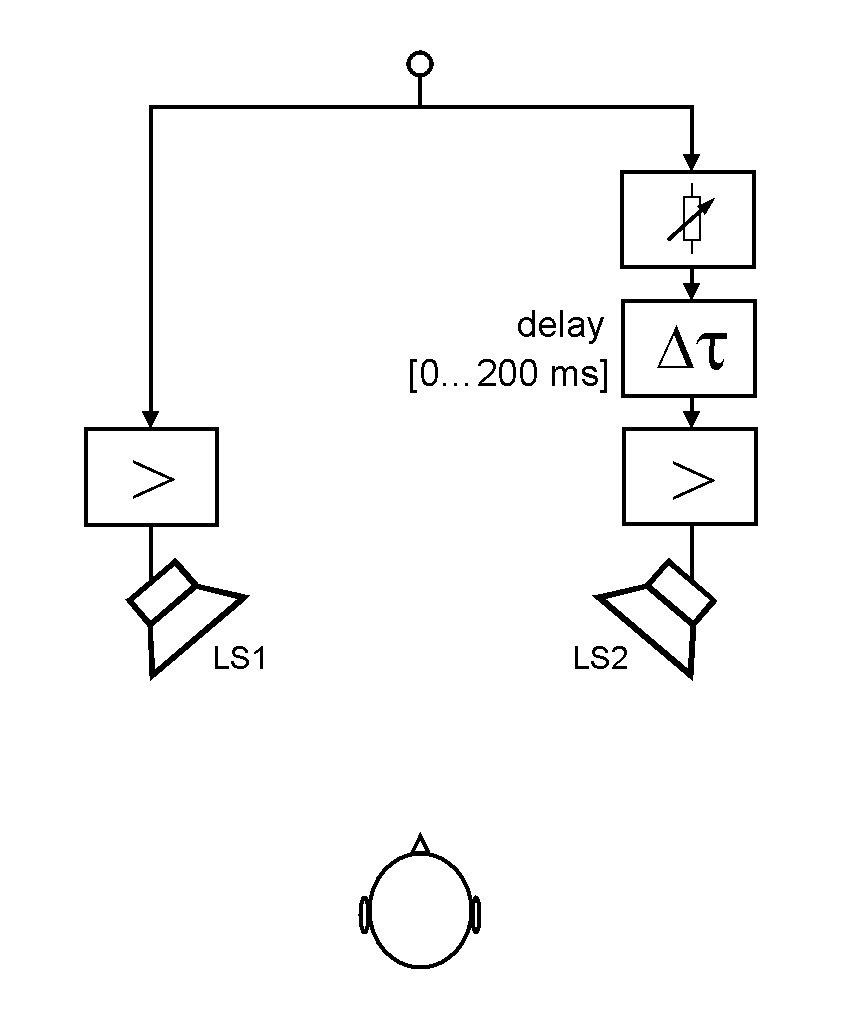

I also want to discuss the Haas Effect. As mentioned earlier, AB stereo miking creates a stereo image by the time difference in sounds arriving at two microphones.

Similarly, what happens if the same sound is played with a time delay between the left and right speakers? The answer is that it will sound biased towards the side that plays first.

This technique can make mono sources sound like stereo. However, from my experience, recording a double take sounds more natural and fuller than creating a stereo image with the Haas Effect.

While it’s useful to know, it’s generally better to use this technique only when necessary.

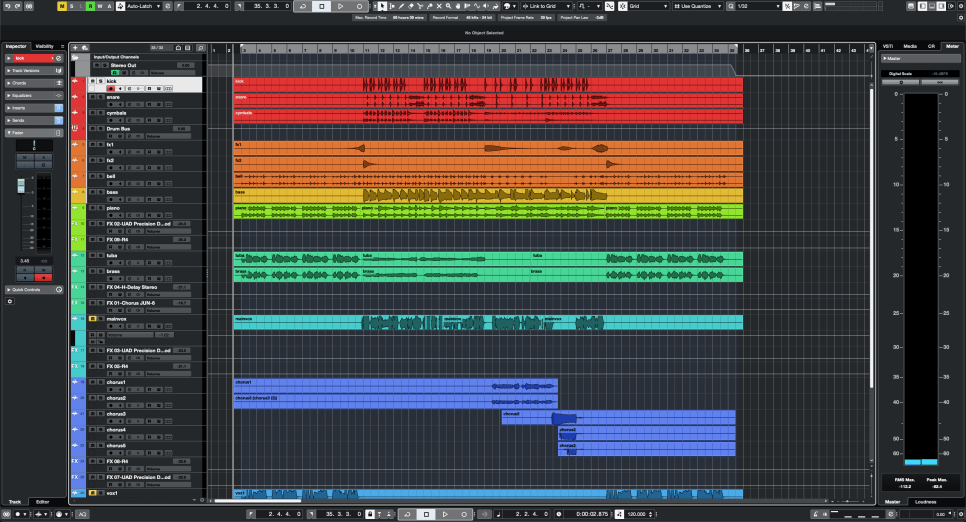

There are various ways to express panning.

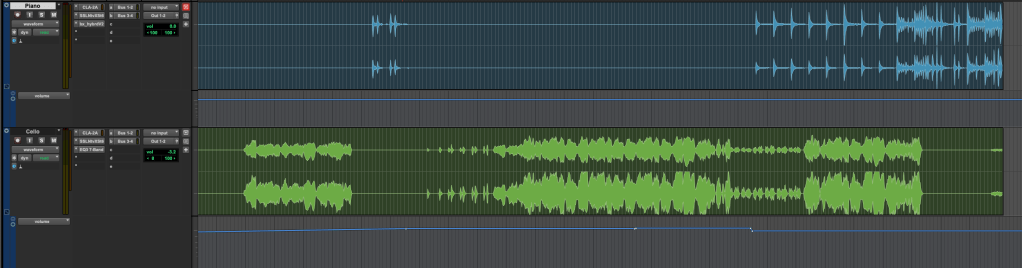

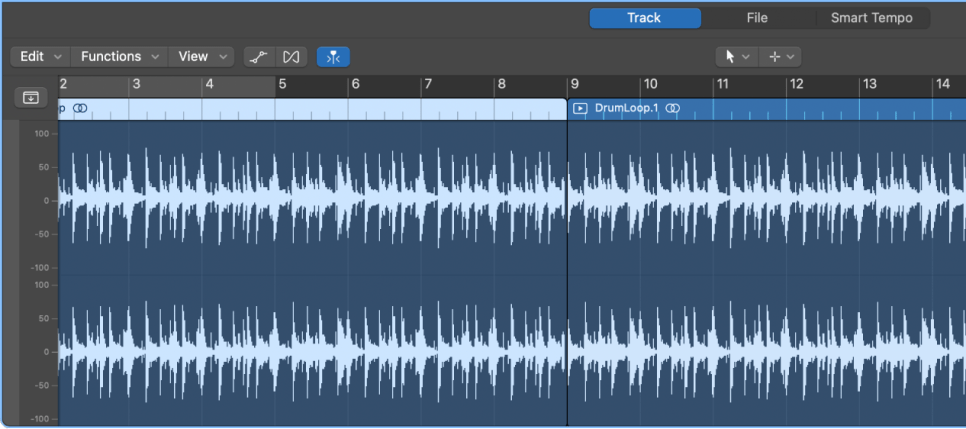

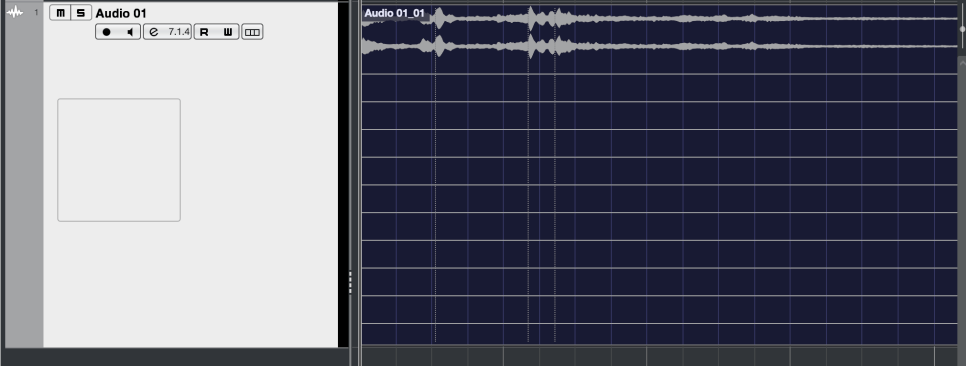

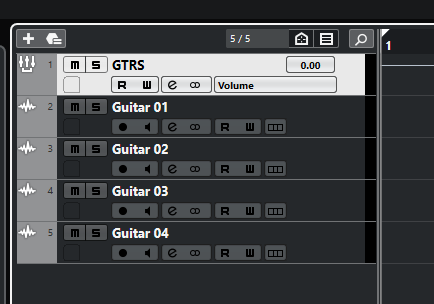

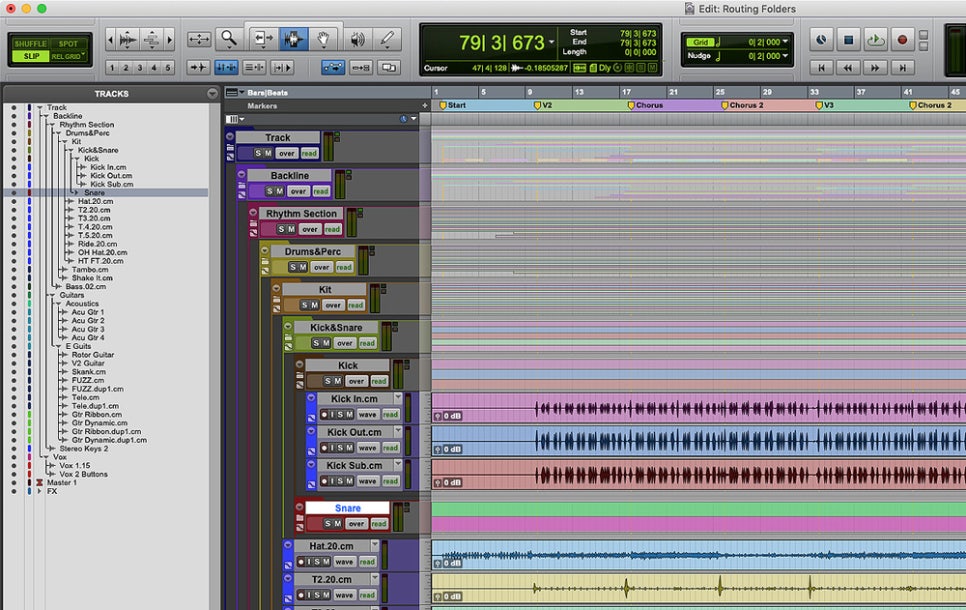

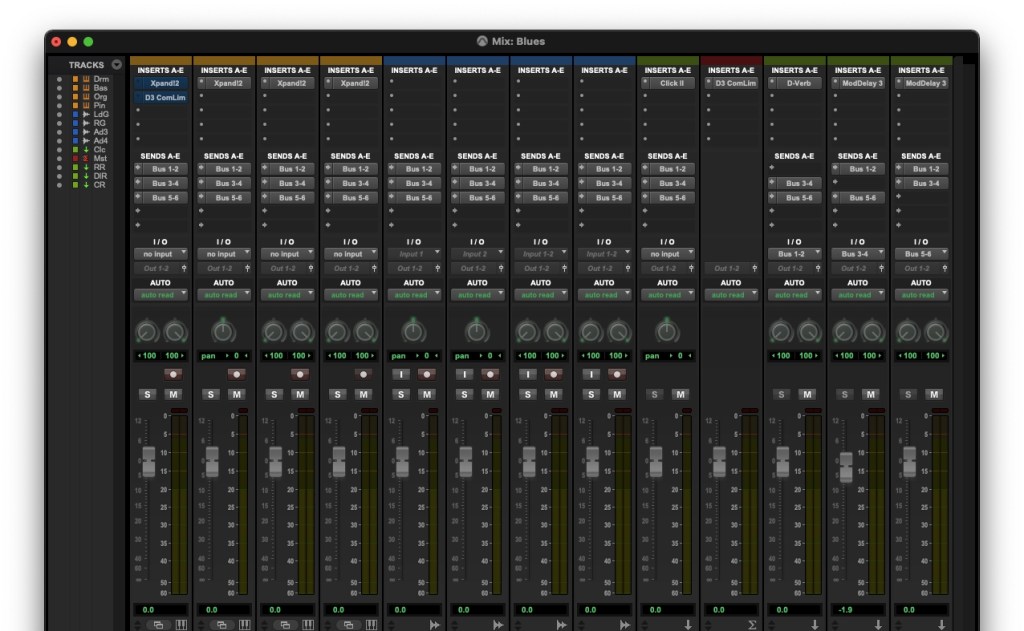

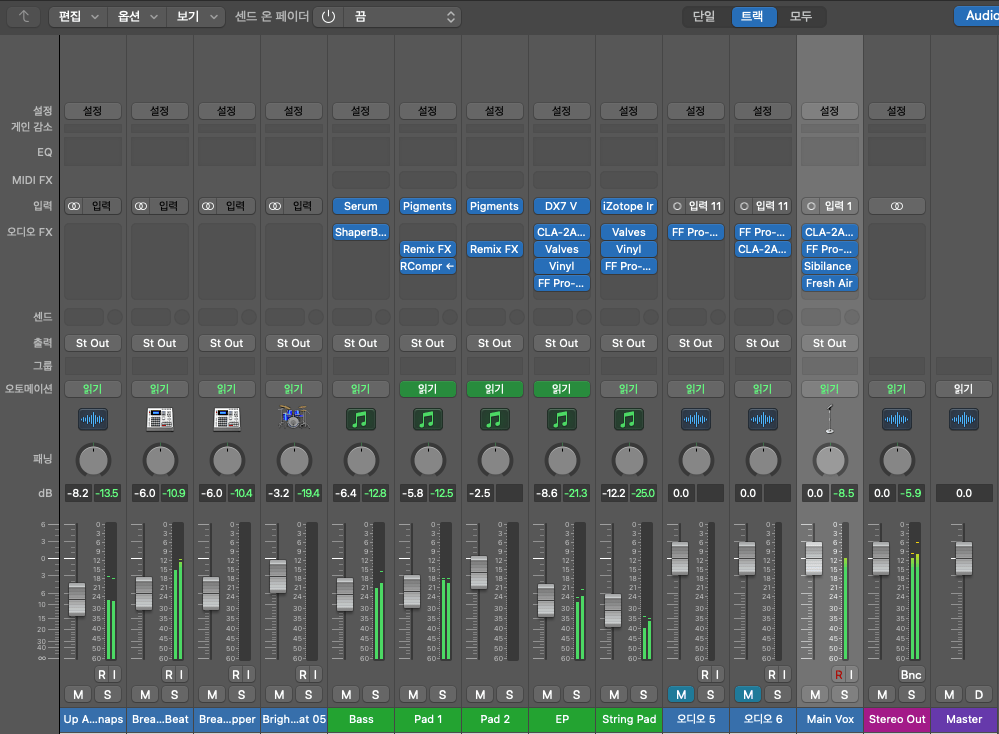

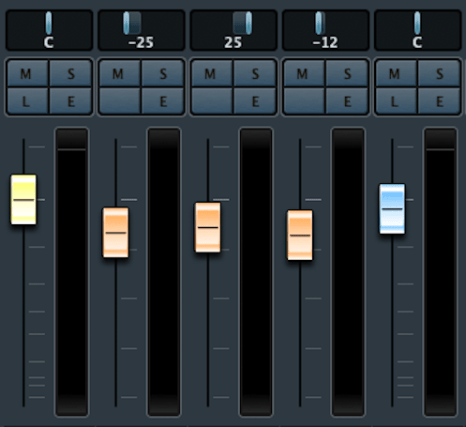

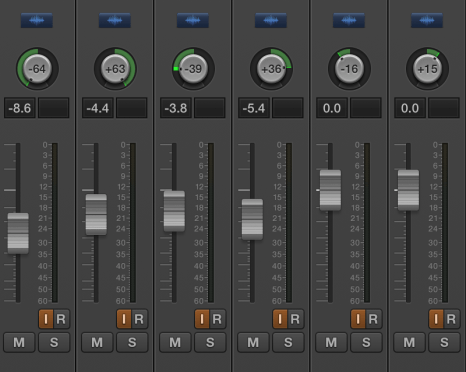

For example, Logic uses a scale from -64 to +63, while Cubase and Pro Tools use -100 to +100. Some DAWs use clock-face representations.

There’s also Balanced Panning, which allows free adjustment of left and right panning.

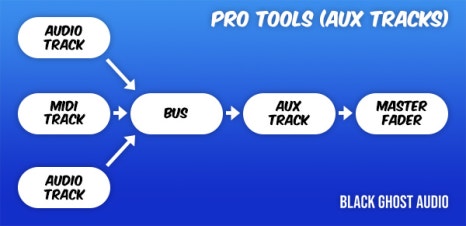

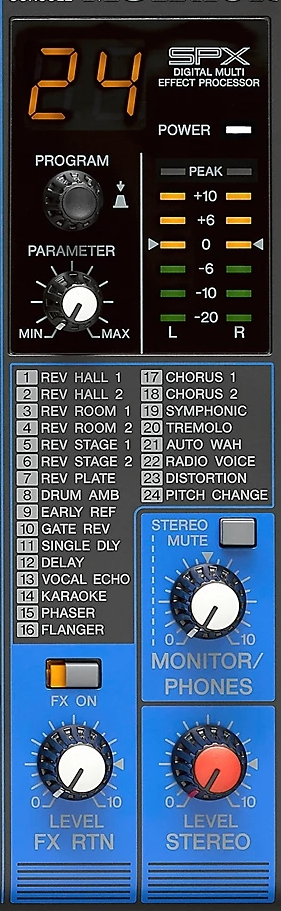

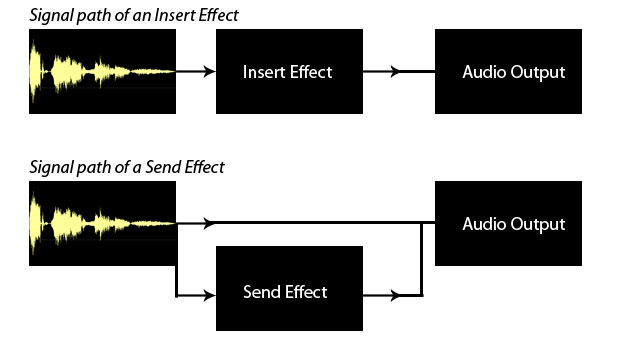

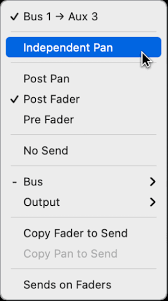

When sending signals externally using Send from a panned source, the panning settings do not apply. Therefore, each DAW provides a Send Panning function to send the signal with the applied panning.

That’s all for today. See you in the next post!