Hello, this is Jooyoung Kim, an engineer and music producer.

There are numerous types of EQs available.

Today, I will describe some of these EQs.

- Cut Filter, Band Pass Filter

- Shelving EQ

- Notch Filter

- Graphic EQ

That’s it for today.

- Parametric EQ

- Dynamic EQ

- Baxandall EQ

1) Cut Filter, Band Pass Filter

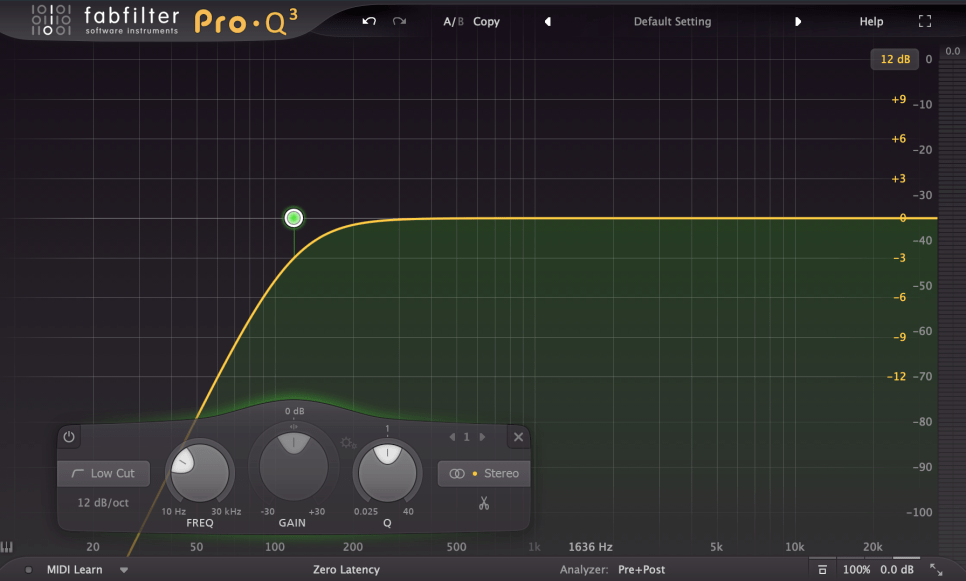

Cut filters are quite common and widely used. Low Cut and High Cut filters are frequently applied.

Low Cut filters are used to reduce low-frequency noises like vibrations from the floor or other low-frequency disturbances.

High Cut filters reduce high frequencies to create a lo-fi sound or to achieve a specific sound characteristic.

Low Cut filters are also known as High Pass filters because they let higher frequencies pass through. Similarly, High Cut filters are known as Low Pass filters.

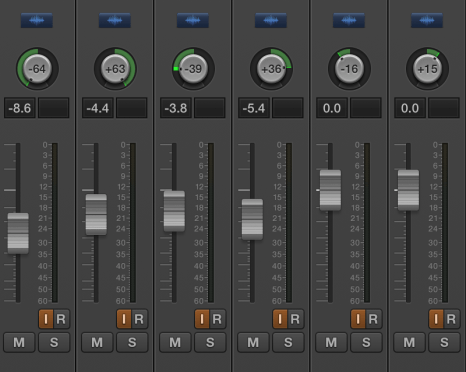

The amount of reduction is often labeled as -6dB per octave (-6dB/oct) or Pole (with 1 Pole equating to -6dB/oct). Typical values include -6dB/oct, -12dB/oct, -18dB/oct, -24dB/oct, and so on.

While not exactly the same, a Band Pass filter can be thought of as a combination of these two filters.

These filters significantly alter the phase.

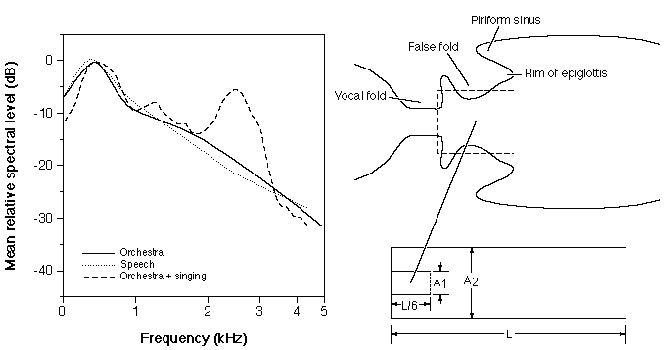

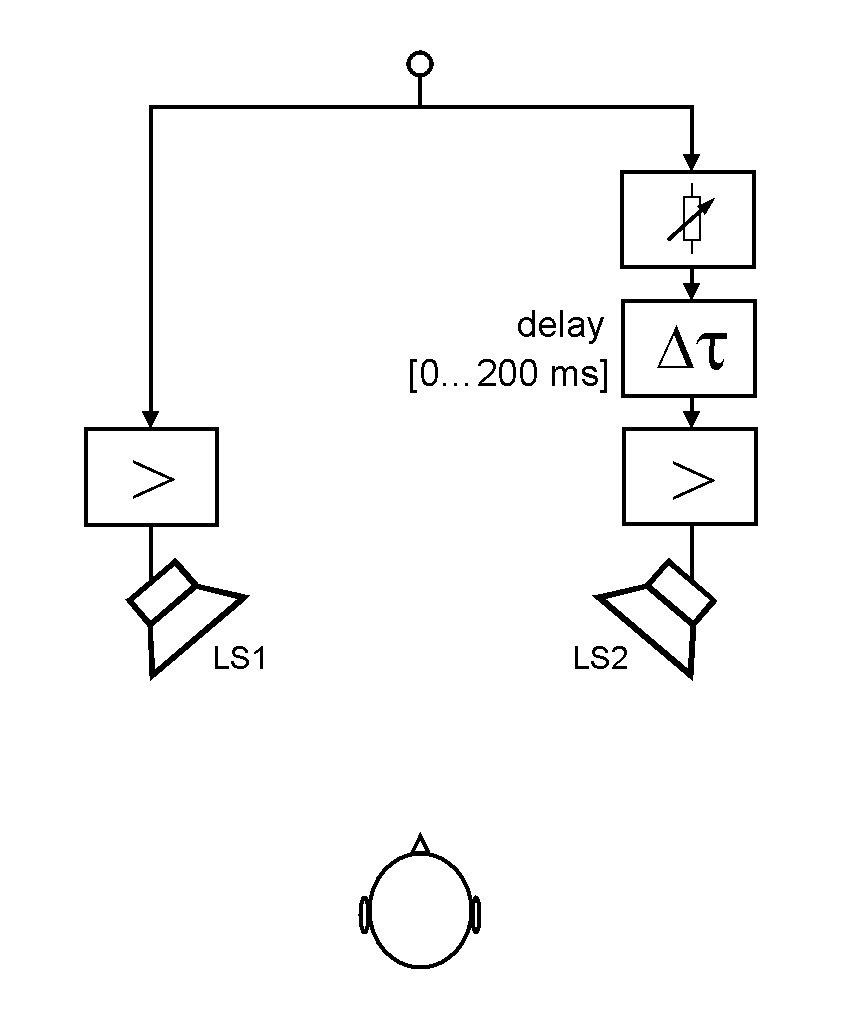

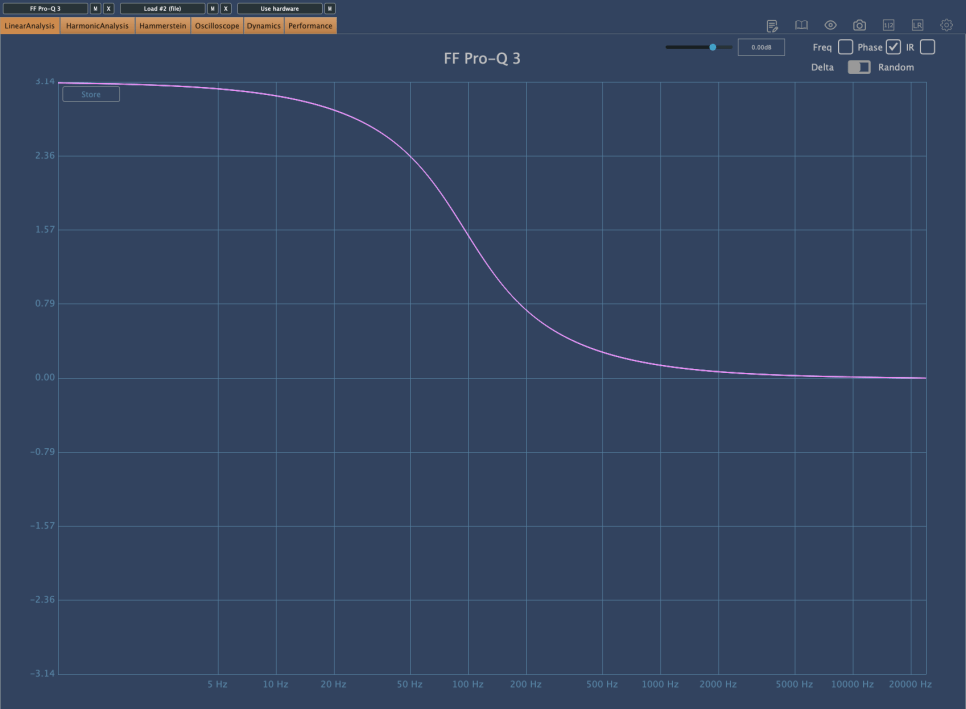

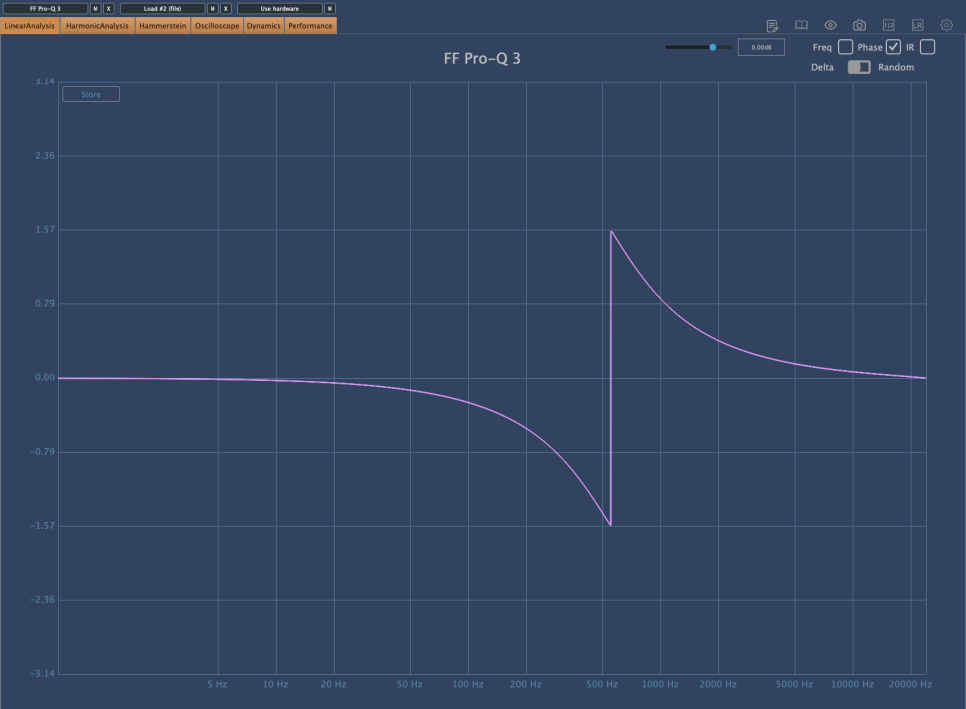

The phase shift graph above shows the phase change when a -12dB/oct Low Cut filter is applied. You can see a phase shift of π (3.14) in the low-frequency range.

Comparing this with other phase graphs, you will realize that this is quite a significant phase shift. A large phase shift means that the sound will be quite different from the original. Therefore, using Cut filters indiscriminately can result in a sound that is far from the intended one.

I have previously discussed issues caused by phase cancellation.

Each Pole causes a phase shift of π/2. Using a steep Low Cut filter like -24dB/oct can result in a phase shift of up to 2π, so it’s generally not recommended to use it excessively.

However, use it when necessary.

2) Shelving EQ

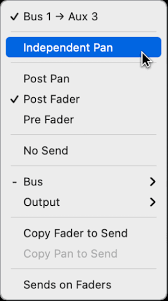

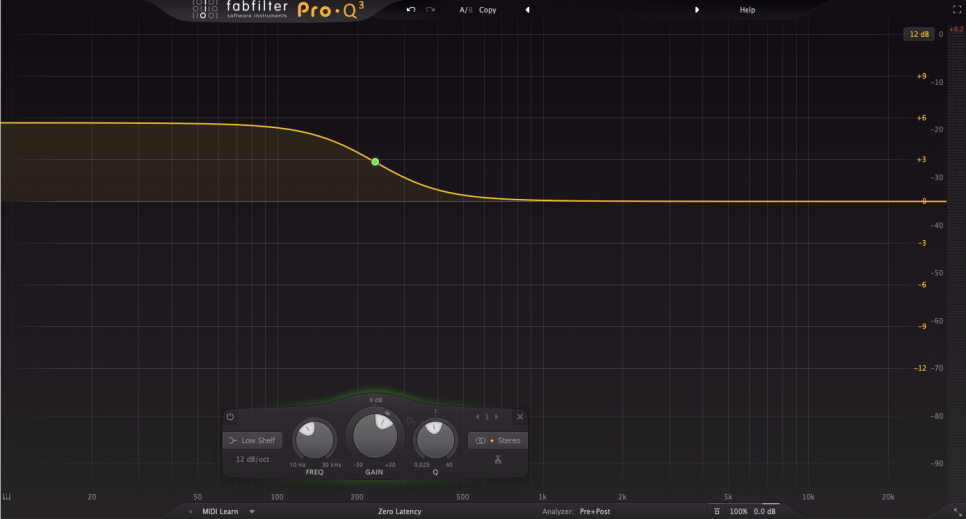

Shelving EQ, also known as Shelving Filter, adjusts the volume of frequencies in a shelf-like shape, as the name suggests.

It is used to lift or lower an entire frequency band.

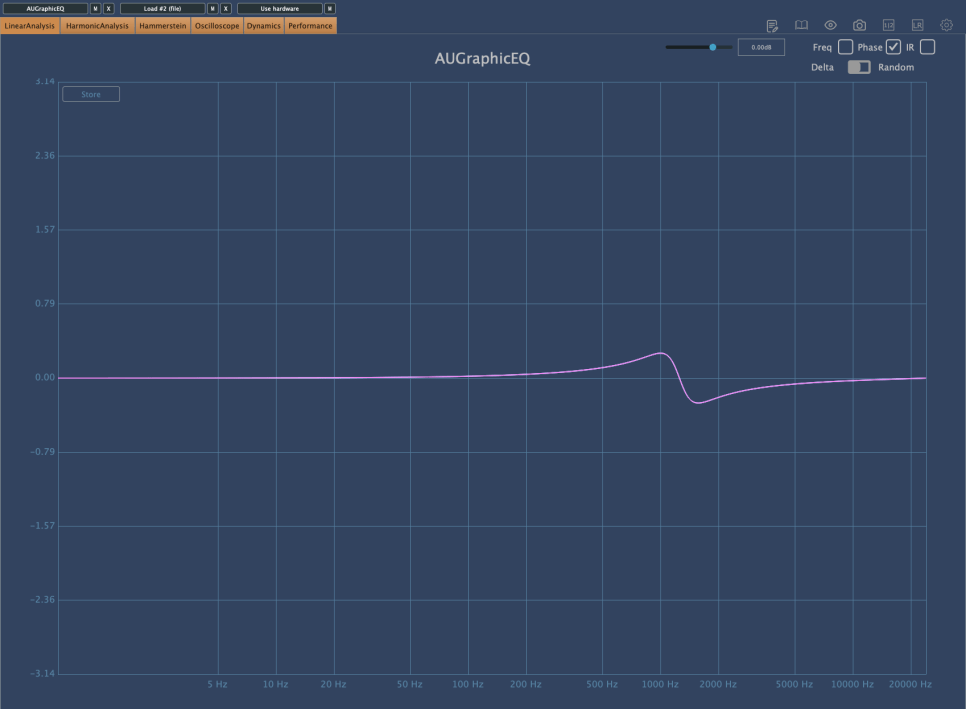

As shown in the image above, Shelving EQs cause less phase shift, making them a good alternative to Cut filters.

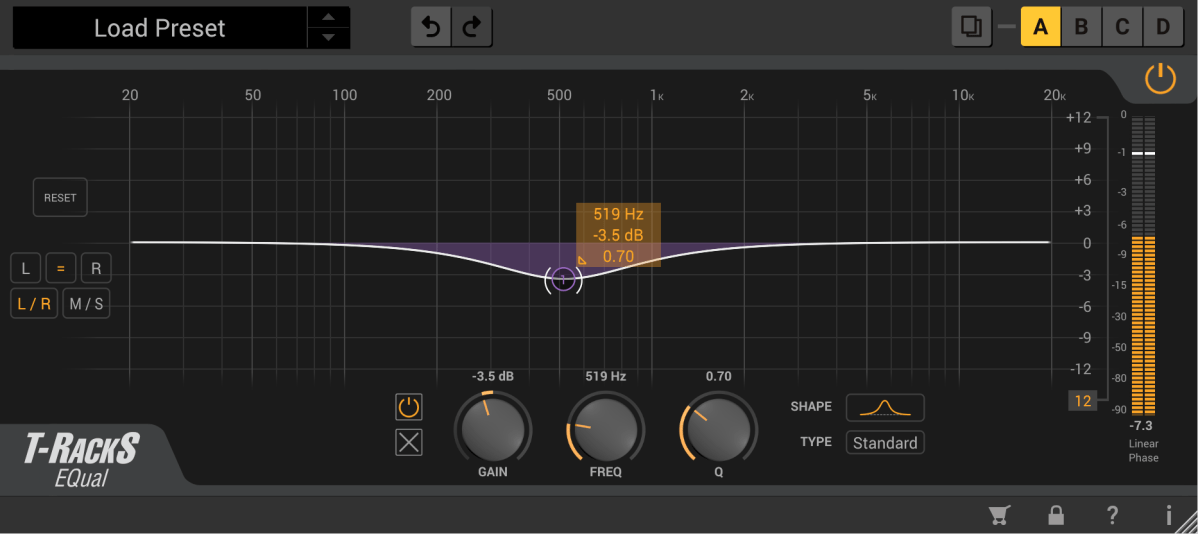

3) Notch Filter

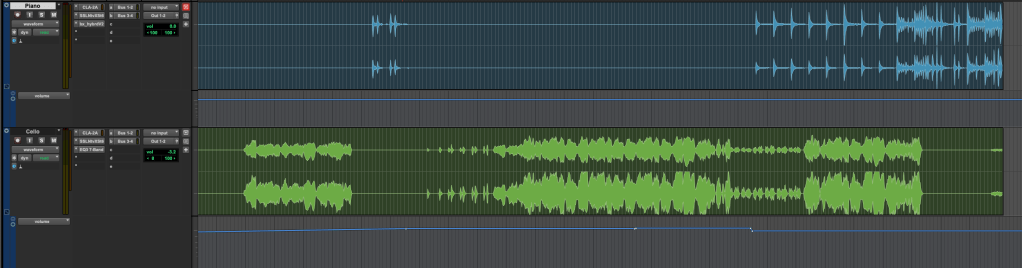

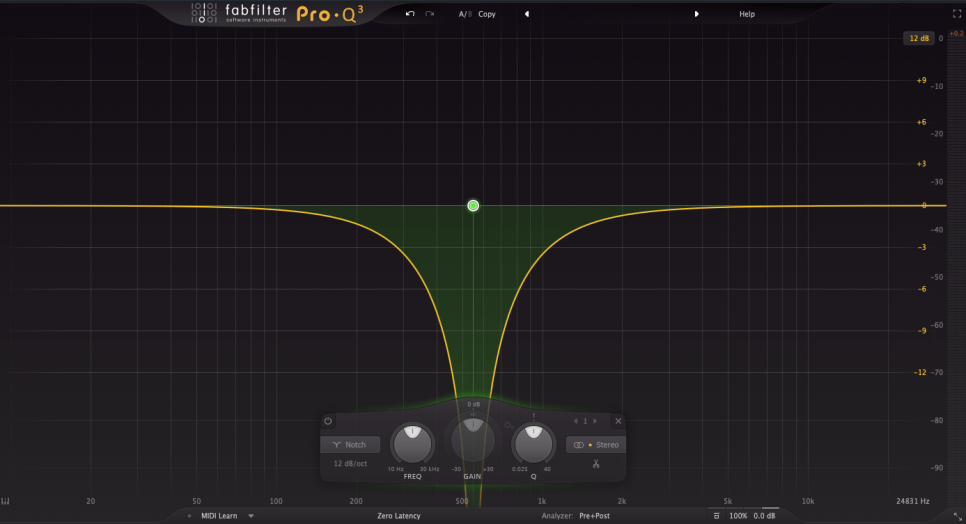

Notch filters can be used to eliminate resonances that are difficult to control with other EQs or to create specific musical effects.

It is quite rare to use Notch filters in mixing. They are typically used for problematic sources that are hard to manage otherwise. I personally use them perhaps once a year in mixing.

In music production, Notch filters can be used on synthesizers to create interesting effects by modulating frequencies over time with an LFO.

4) Graphic EQ

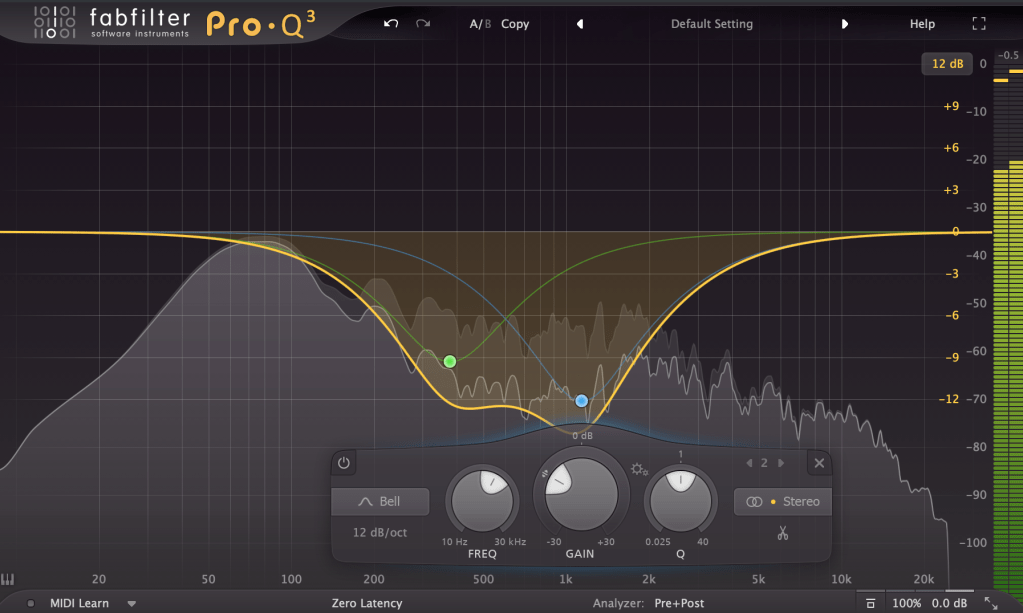

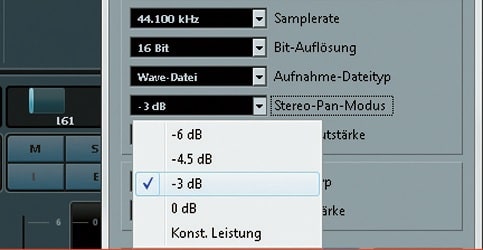

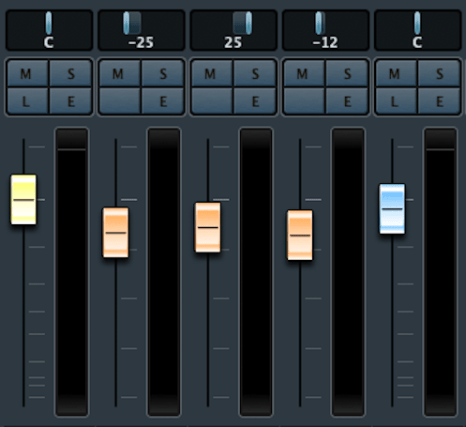

With a Constant Q setting, the Q value remains the same as the volume changes. With a Variable (Non-Constant) Q setting, the Q value changes with the volume adjustments.

These internal settings are usually described in the manual, so it’s best to read it for proper usage.

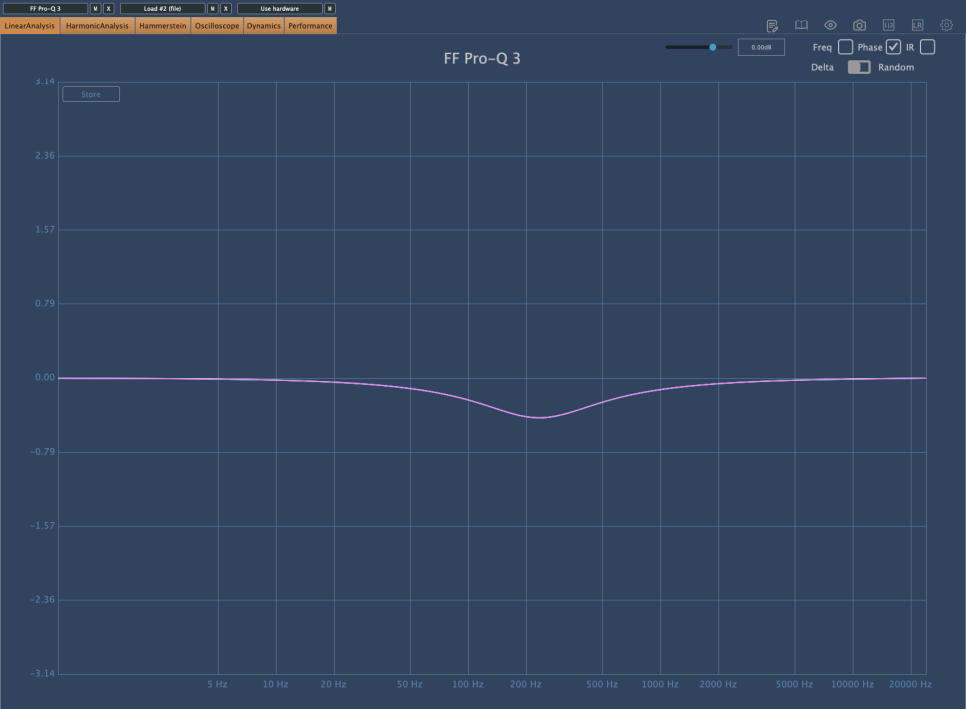

The phase shift is minimal. The common Bell-type Parametric EQ, which I will explain next time, also changes phase in a similar way.

In studio mixing, Graphic EQs are rarely used due to convenience. However, knowing these theories might be useful, especially if you also do live mixing.

Describing Parametric EQ, Dynamic EQ, and Baxandall EQ would make this post too long, so I will continue in the next article.

The main point I wanted to convey today is the importance of considering phase changes when using EQs.

If the sound is different from what you intended after adjusting the frequencies, it is often due to phase changes.

If it sounds good to your ears, that’s what matters. However, understanding what to watch out for and why can lead to more efficient and faster decision-making.

See you in the next post!