Hello, I’m Jooyoung Kim, a mixing engineer and music producer.

Today, I want to talk about how analog sound signals are digitized in a computer.

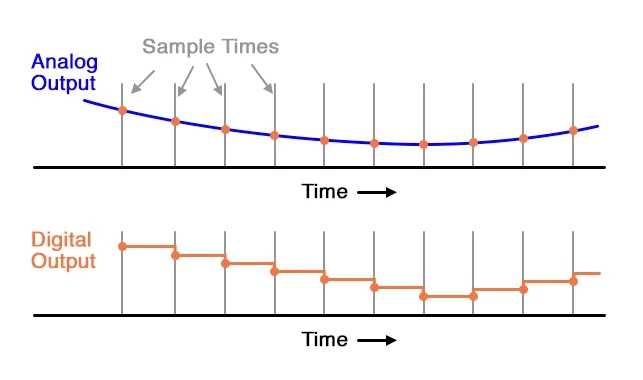

The electrical signals outputted through a microphone preamp or DI box are continuous analog signals. Since computers cannot record these continuous signals, they need to be converted into discrete signals. This is where the ADC (Analog to Digital Converter) comes into play.

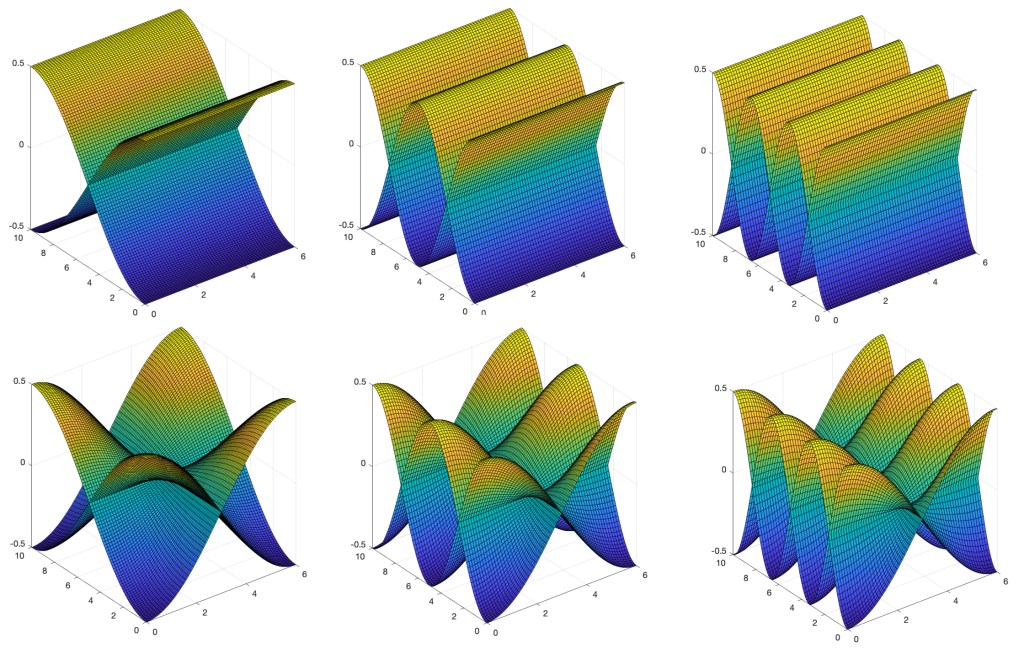

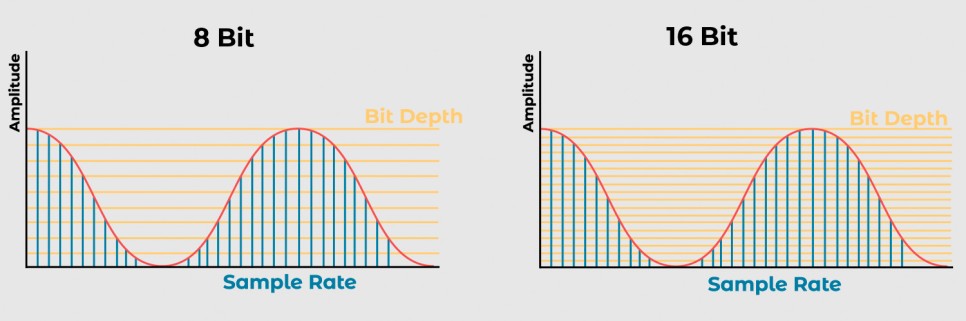

Here, the concepts of Sample Rate and Bit Depth come into the picture.

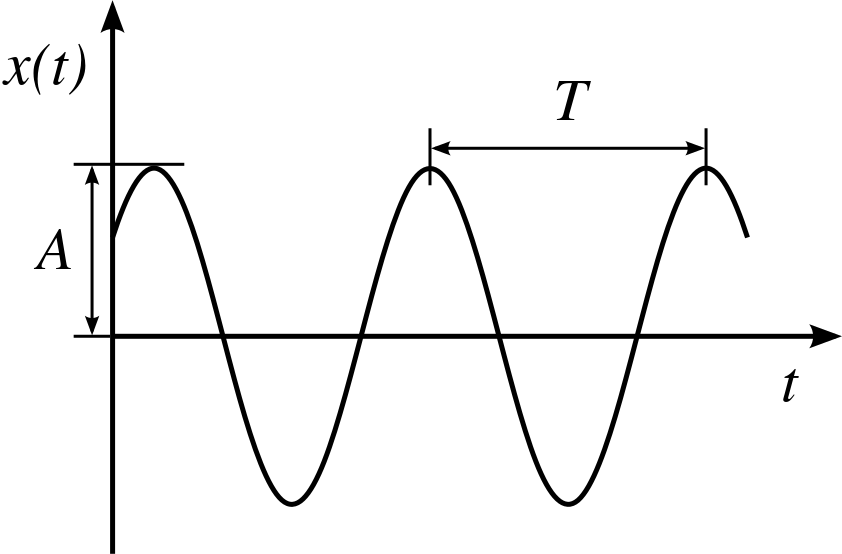

The sample rate refers to how many times per second the signal is sampled.

The bit depth refers to how finely the amplitude of the electrical signal is divided.

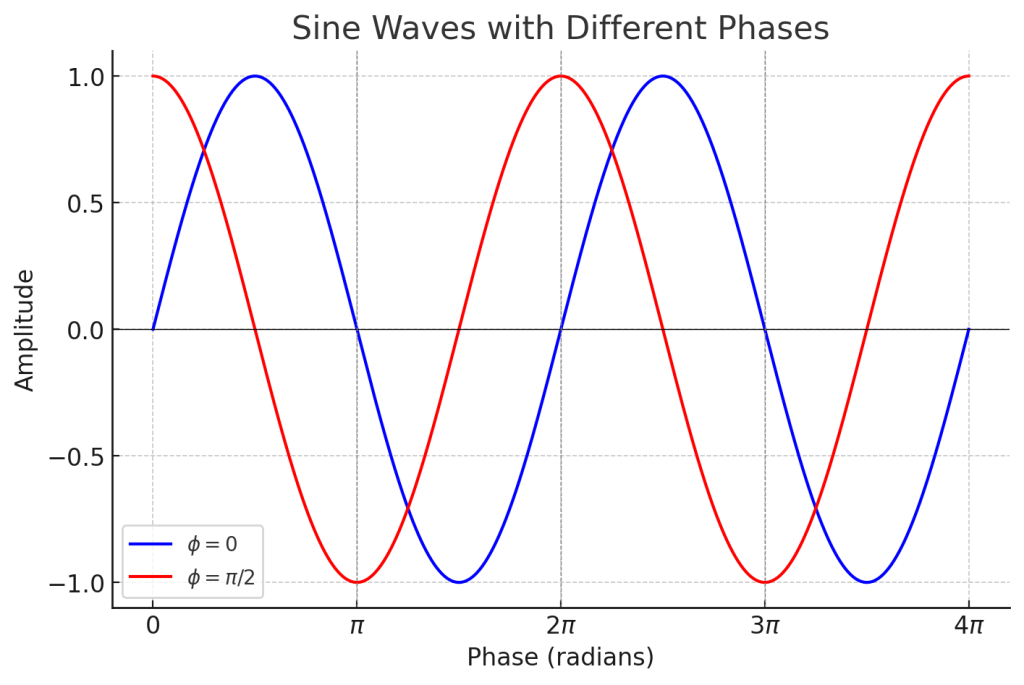

For example, consider a WAV file with a sample rate of 44.1kHz and a bit depth of 16 bits. This file records sound by sampling it 44,100 times per second and divides the amplitude into 65,536 levels (2^16).

A file with a sample rate of 48kHz and a bit depth of 24 bits samples the sound 48,000 times per second and divides the amplitude into 16,777,216 levels (2^24).

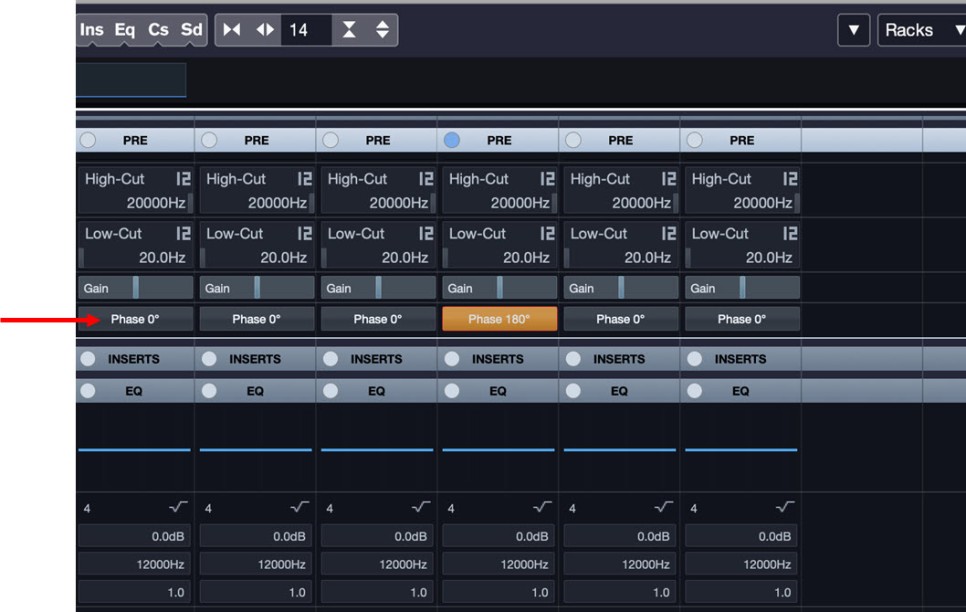

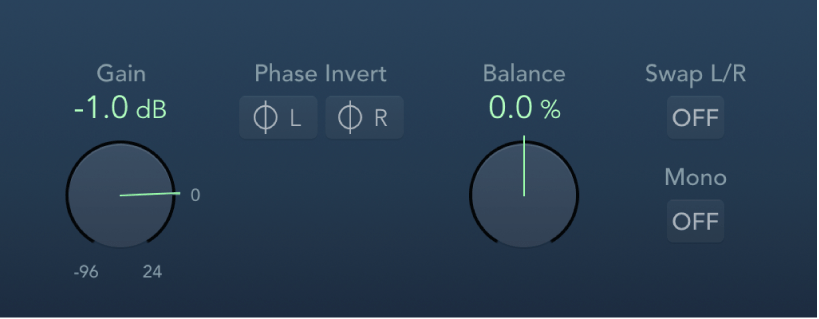

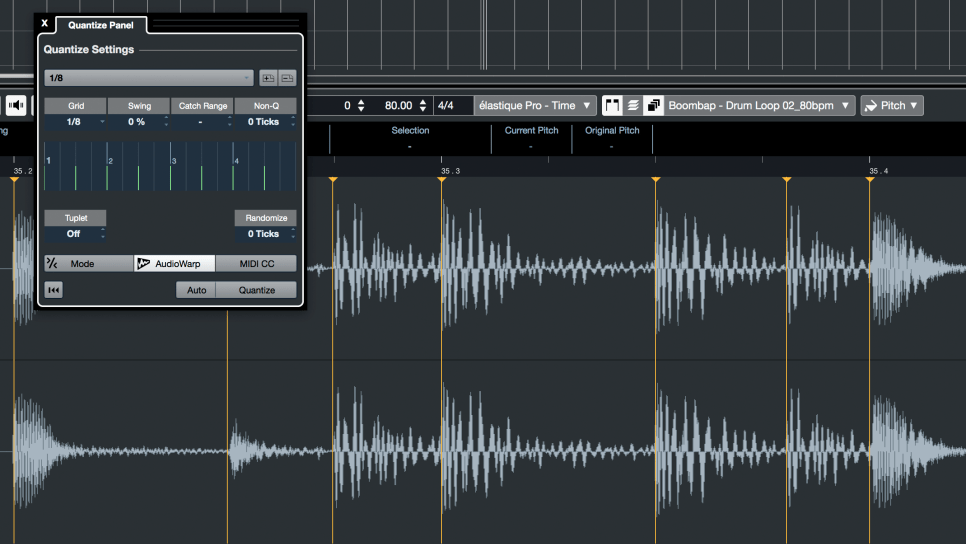

In a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), these digital signals are manipulated. To listen to these digital signals, they need to be converted back into analog electrical signals.

This conversion is done by the DAC (Digital to Analog Converter), often referred to as a “DAC”.

The image above shows a simple DAC circuit that converts a 4-bit digital signal into an analog signal.

These analog signals can pass through analog processors like compressors or EQs and then go back into the ADC, or they can be sent to the power amp of speakers to produce sound.

Audio interfaces contain these converters, along with other features like microphone preamps, monitor controllers, and signal transmission to and from the computer, making them essential for music production.

However, those who do not need input functionality might use products with only DAC functionality.

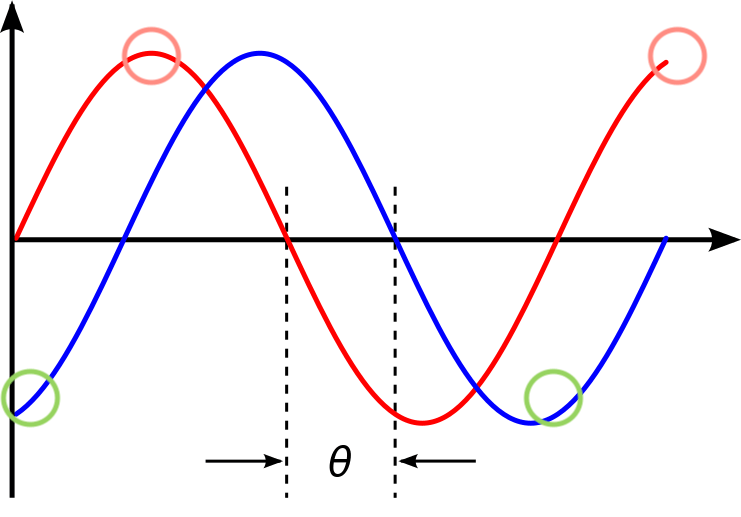

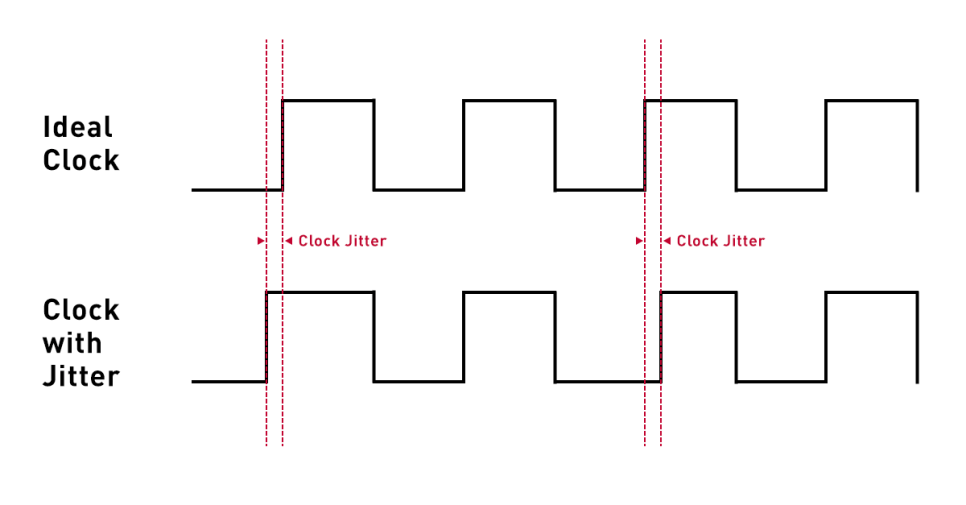

Inside these digital devices, there are usually IC chips that use a signal called a Word Clock to synchronize different parts of the circuit.

To synchronize this, devices called Clock Generators or Frequency Synthesizers are used.

In a studio, there can be multiple digital devices, and if their clocks are not synchronized, it can cause a mismatch called jitter. Jitter can result in unwanted noises like clicks or cause the sound to gradually shift during recording (I experienced this while recording a long jazz session in a school studio where the master clocks of two devices were set differently).

To prevent this, digital devices are synchronized using an external clock generator. If you are not using multiple digital devices, the internal clock generator of the device should suffice, and there is no need for an external clock generator.

An article in the journal SOS (Sound On Sound) even mentioned that using an external clock generator does not necessarily improve sound quality.

Today, we covered Sample Rate, Bit Depth, ADC (Analog to Digital Converter), DAC (Digital to Analog Converter), Word Clock, and Jitter.

While these fundamental concepts can be a bit challenging, knowing that they exist is essential if you’re dealing with audio and mixing. If you find it difficult, just think, “Oh, so that’s how it works!” and move on.

See you in the next post!