Hello, this is Jooyoung Kim—sound engineer and music producer.

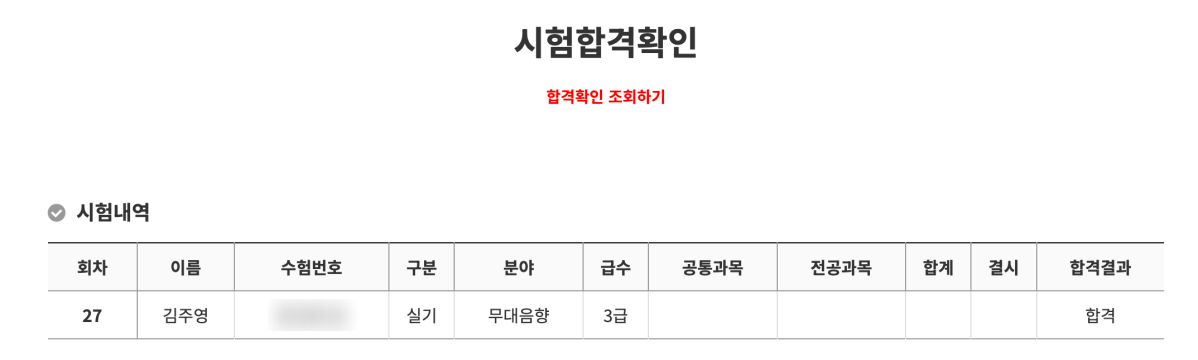

In Korea, there is a government-issued certification called Stage Sound Engineer (Level 3, 3 is the first (or beginner) level, followed by 2 and 1.).

It doesn’t have a direct equivalent in the US, UK, or Canada, but you can think of it as something like a formal audio engineering license, proving both practical and theoretical knowledge in live sound.

As I’ve been working in the audio field, I realized that while practical skills are essential, having an official certification also helps when listing credentials on a résumé. For a long time, I wasn’t sure if it was worth pursuing—but I figured if I didn’t get it this year, it would only become harder later. So, I decided to take the exam.

Studying for the Written Exam

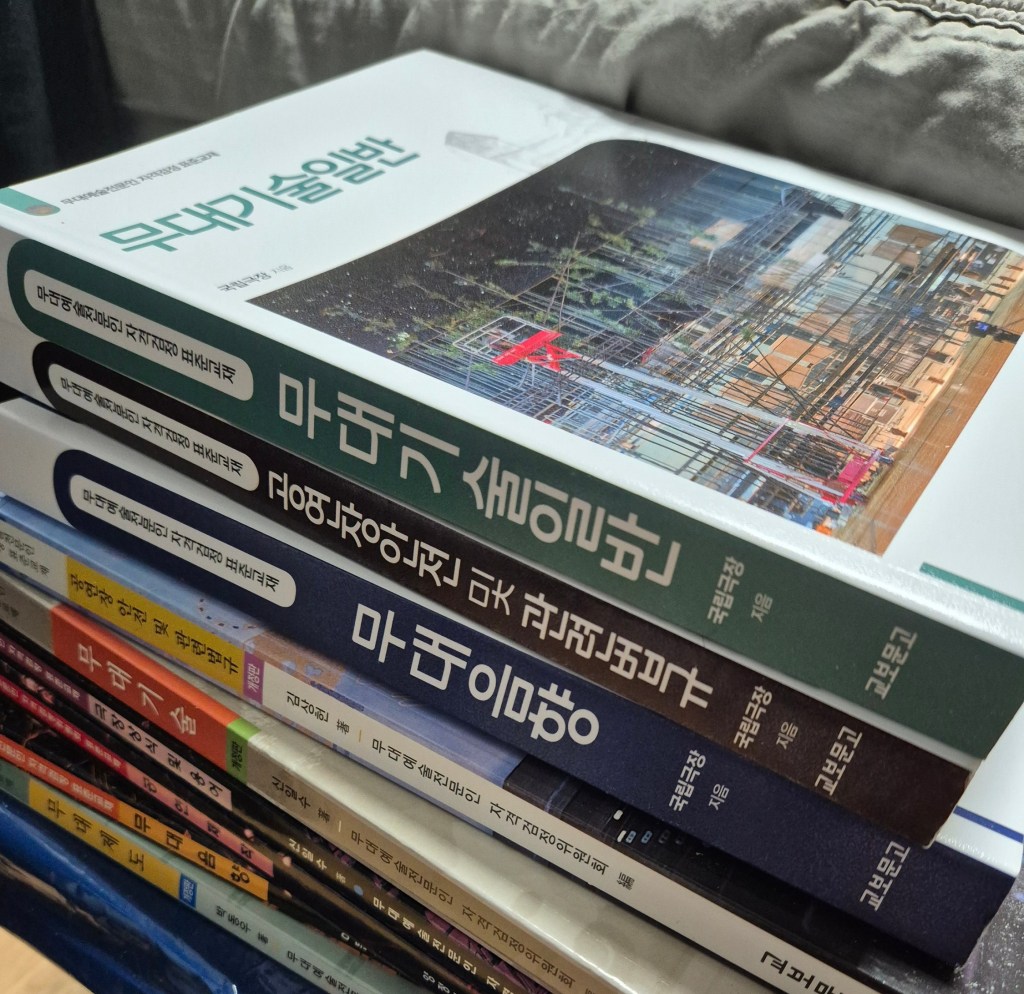

I had already bought some textbooks back when I ambitiously wanted to “master all of audio engineering.”

Unfortunately, the exam content had been updated recently, which meant my older materials were out of date.

At first, I tried to get by without buying the new edition, but after checking last year’s exam questions, I realized too many things had changed. So, I finally bought the updated books just two days before the exam and studied them intensely.

In total, I prepared for about ten days—definitely a crash course. The audio-related parts were manageable thanks to my background, but the legal regulations and stage-specific terminology were quite difficult. Memorization has never been my strong suit (even in English vocabulary study these days, I struggle a lot!).

I didn’t go through the entire book cover to cover, but I solved past exams one set per day and focused on reviewing the parts I got wrong. It was a very “efficient cramming” strategy.

The Practical Exam

Since much of the practical portion overlapped with my usual work, I didn’t need to prepare too heavily.

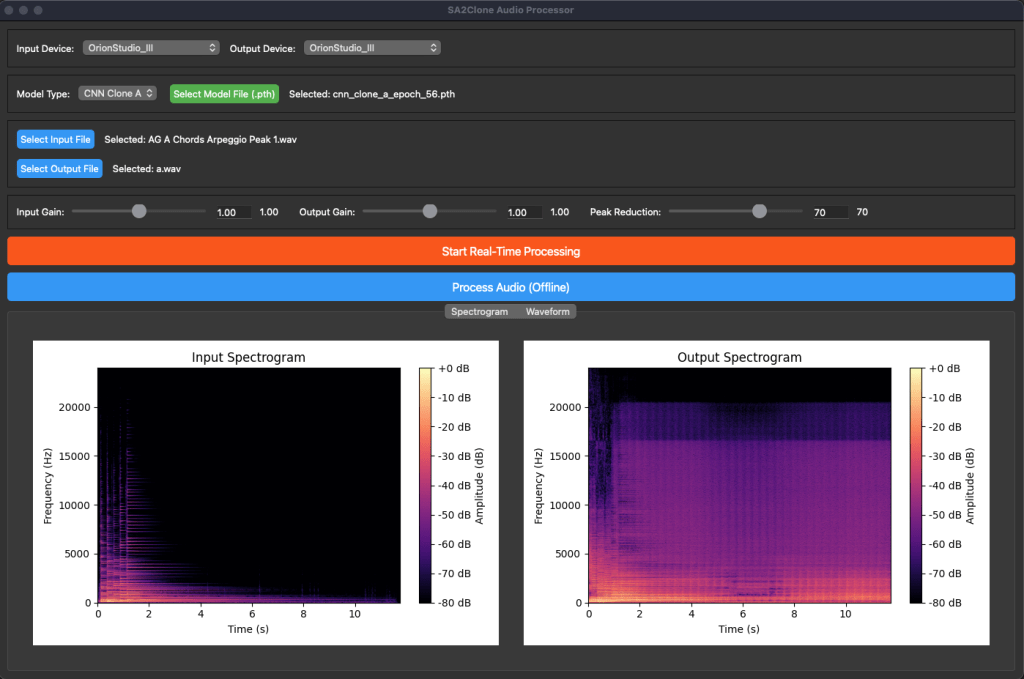

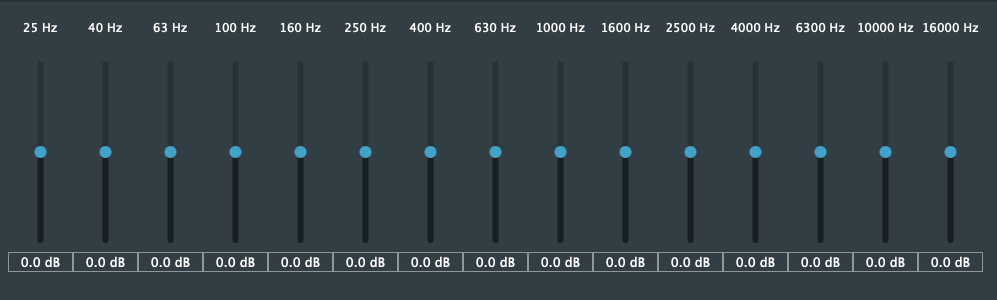

The main part was a listening test: adjusting pink noise with a 15-band graphic EQ to balance different frequency ranges, and identifying test tones across the EQ bands.

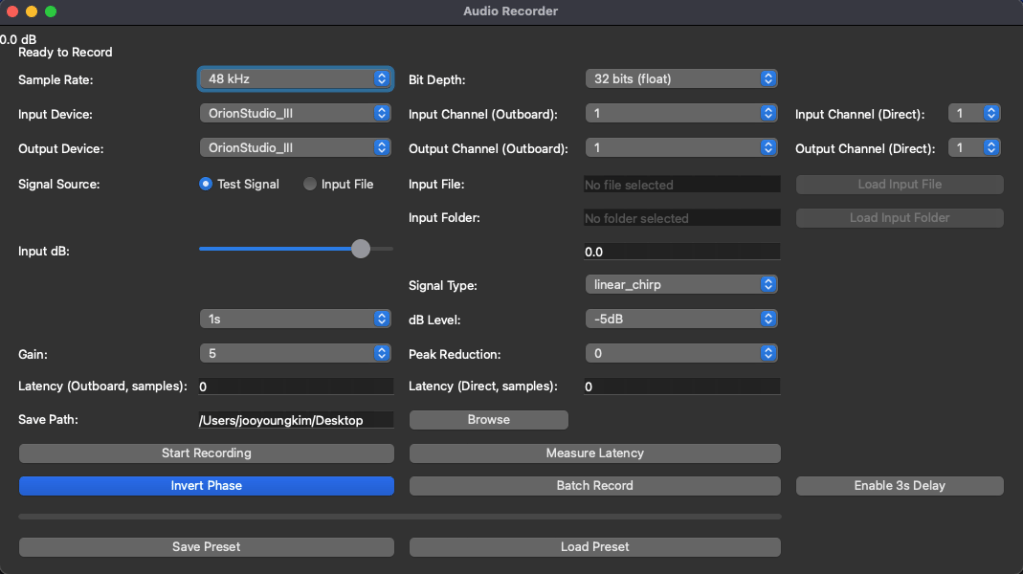

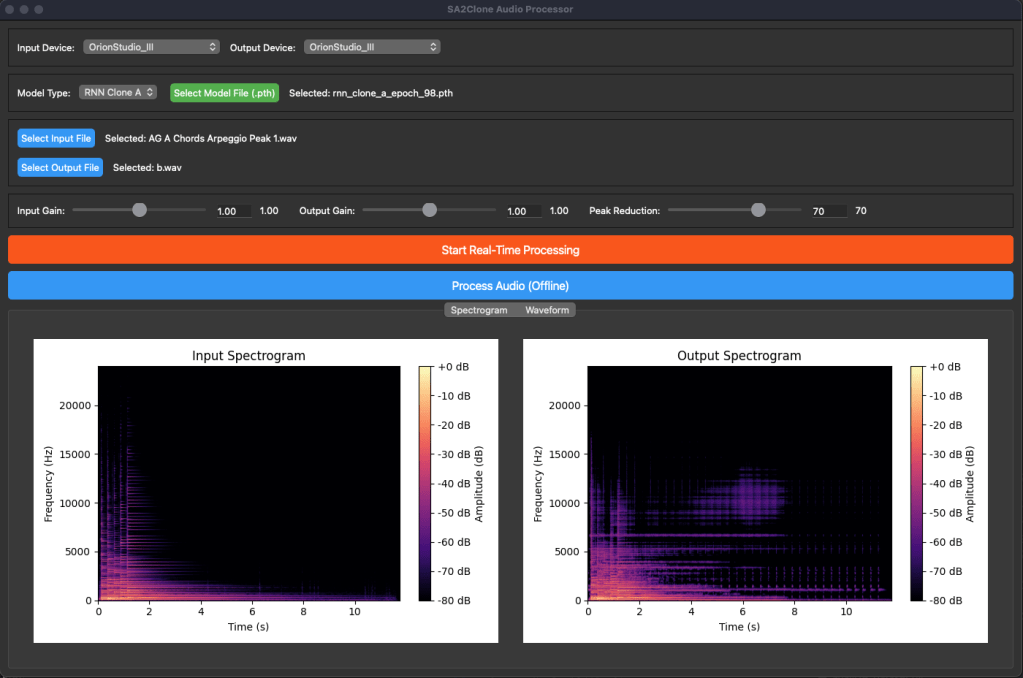

Because I couldn’t find a simple 15-band graphic EQ plugin anywhere, I actually built one myself as a VST3 and AU plugin. If anyone needs it, I uploaded it here:

🔗 GitHub – JYKlabs/15-Band-Graphic-EQ

Mac users can simply extract the files and place them in /Library/Audio/Plug-Ins/VST3 and /Library/Audio/Plug-Ins/Components.

Windows users can place the VST3 file in their VST3 plugin directory. (Since I only built it on Mac, I haven’t tested it on Windows yet.)

The plugin is extremely minimal—no extra features, just a straightforward EQ.

During the actual exam, there were 10 listening questions in total. The first five (identifying effects) were fairly easy, but the last five (detecting EQ adjustments applied to music or noise) were much harder. Since the exam environment was different from my usual studio setup, I struggled a bit.

Also, I tend to think of EQ in terms of musical intervals, but the test was structured entirely in octave relationships, which threw me off at first.

Still, since passing only required 6 correct answers out of 10, I managed to make it through. Thankfully, my hearing was in decent condition that day (sometimes ear fatigue can really mess me up).

Final Thoughts

Unlike in South Korea, many Western countries don’t offer official government-issued certifications specifically for live or stage sound engineering. Instead, recognition and credibility often come from trusted industry certifications, educational credentials, or portfolio evidence.

For example, the Certified Audio Engineer (CEA) credential from the Society of Broadcast Engineers (SBE) is well-regarded and requires both experience and passing a technical exam. For those focused on live sound, programs like Berklee’s Live Events Sound Engineering Professional Certificate offer structured, practical training.

Even if you already have solid skills, it can sometimes be difficult to secure projects or convince clients without something official to show. That’s where certifications and structured programs help: they provide a clear, external validation of your abilities and open doors that pure experience alone may not.

At the end of the day, audio work is unpredictable: sometimes you’re mixing in a studio, other times you’re troubleshooting live sound under pressure. The more prepared you are, the easier it is to adapt.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you in the next post!