Hello, this is Jooyoung Kim, an engineer and music producer.

Today, I’d like to discuss a crucial aspect to consider when adjusting EQ: phase issues.

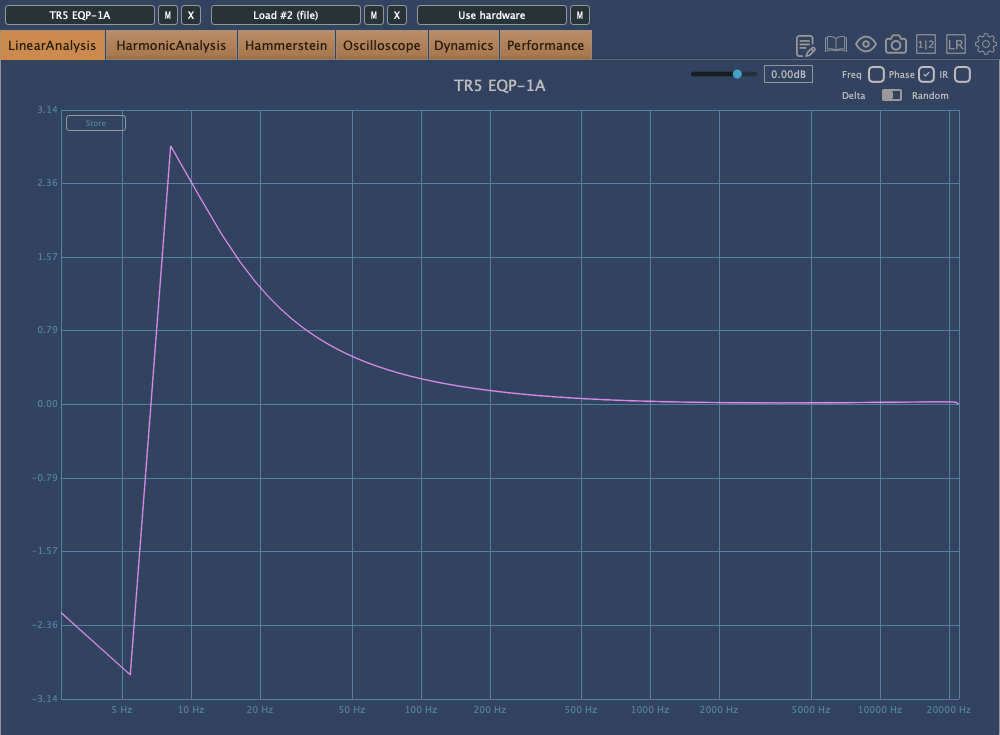

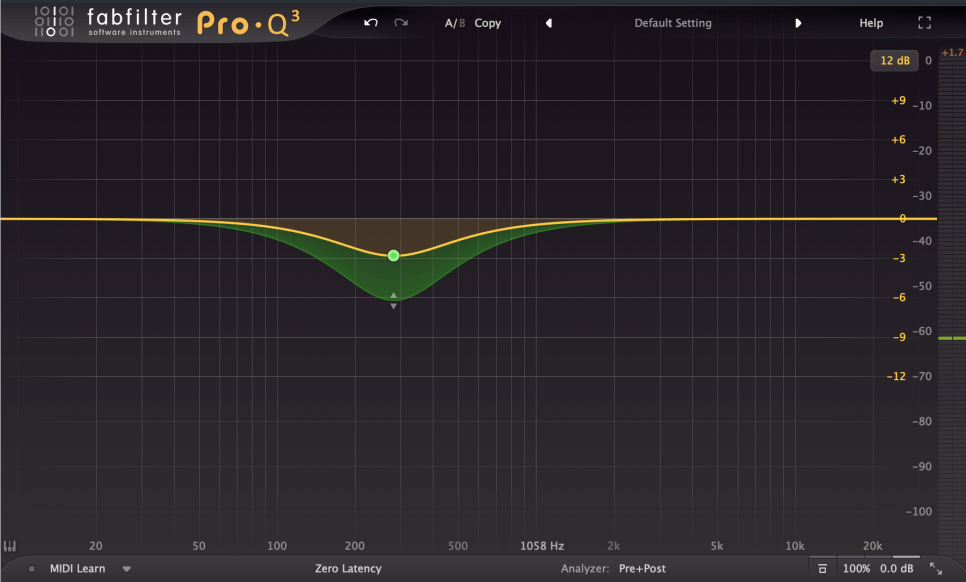

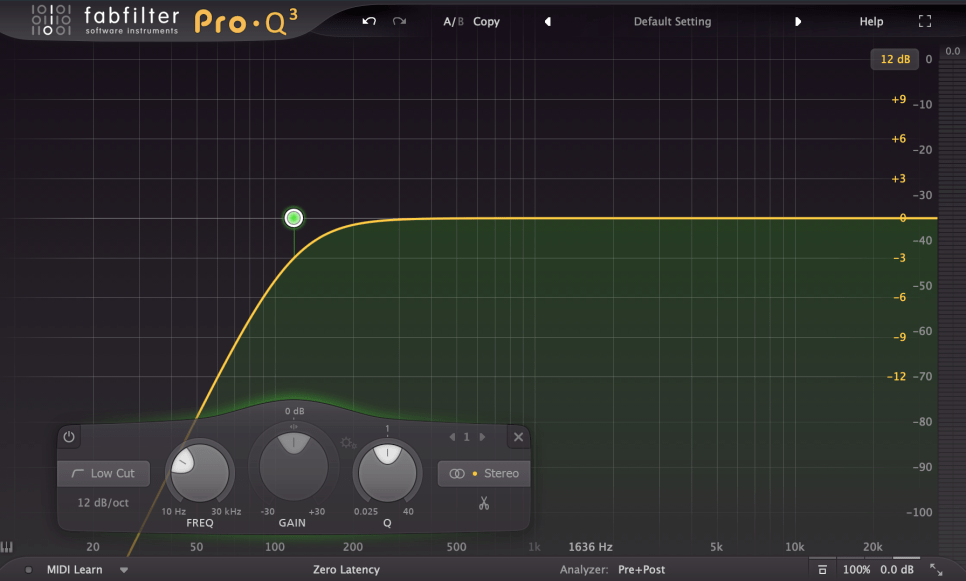

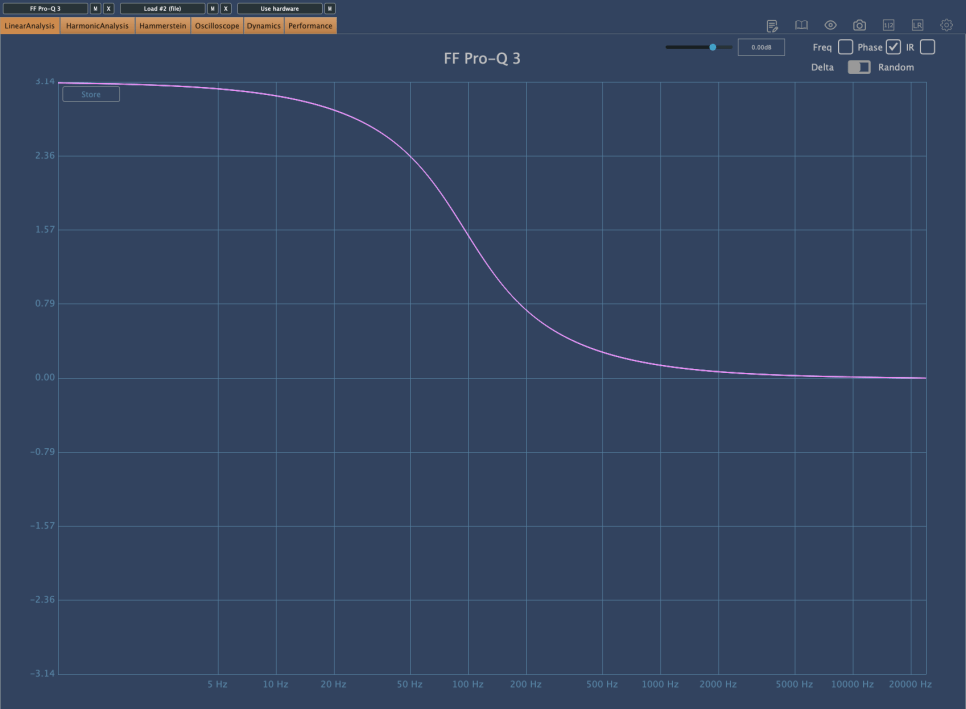

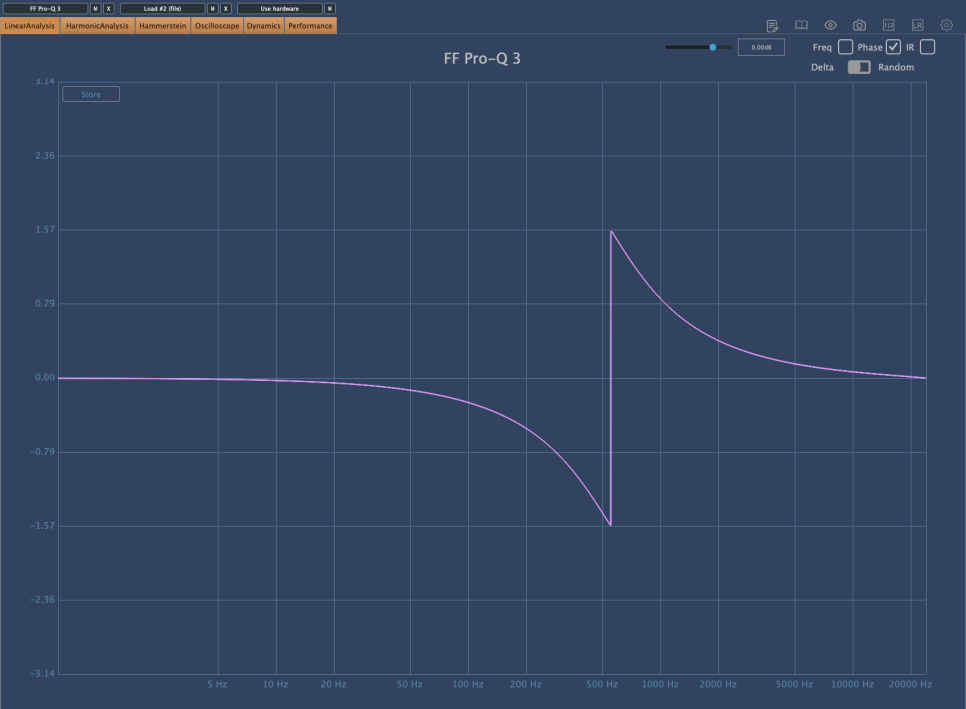

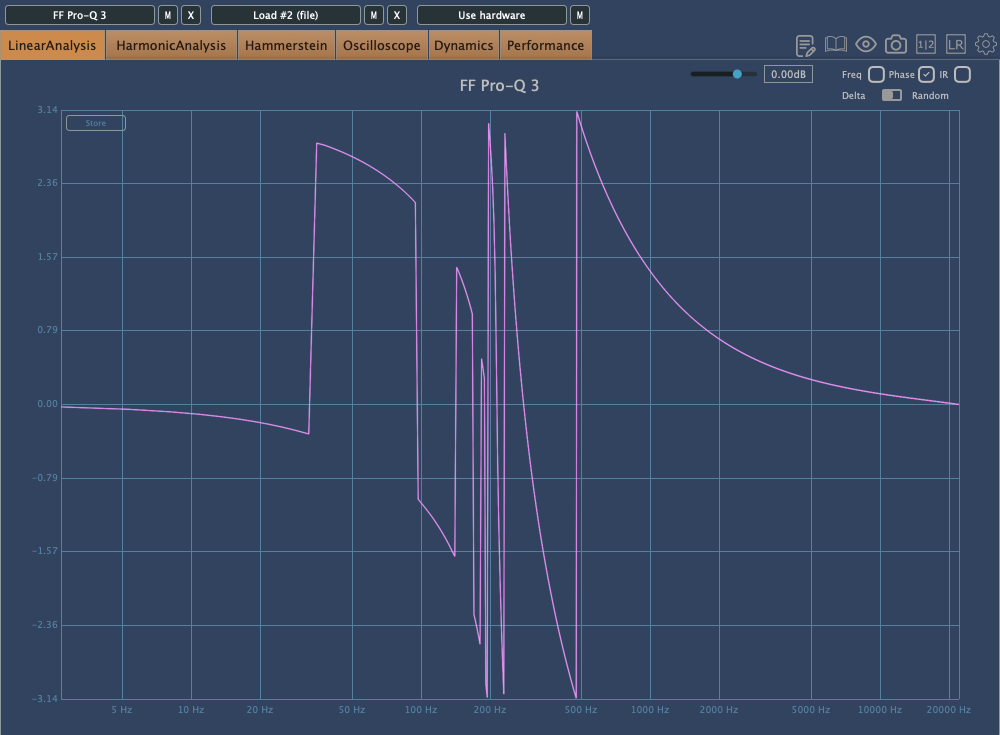

The image above shows the phase change graph when using the Brickwall feature in Fabfilter Pro Q3.

Phase change is generally represented as a continuous line. However, when drawing the graph continuously, the size becomes too large, so the vertical range is usually set to 2π, and the line continues from the top or bottom when it breaks. It’s quite difficult to explain in words.

Anyway, considering such factors, the jagged phase changes can still significantly affect the sound. Extreme phase changes can make the sound seem as if an unintended modulation effect is applied, so it’s important to use it carefully.

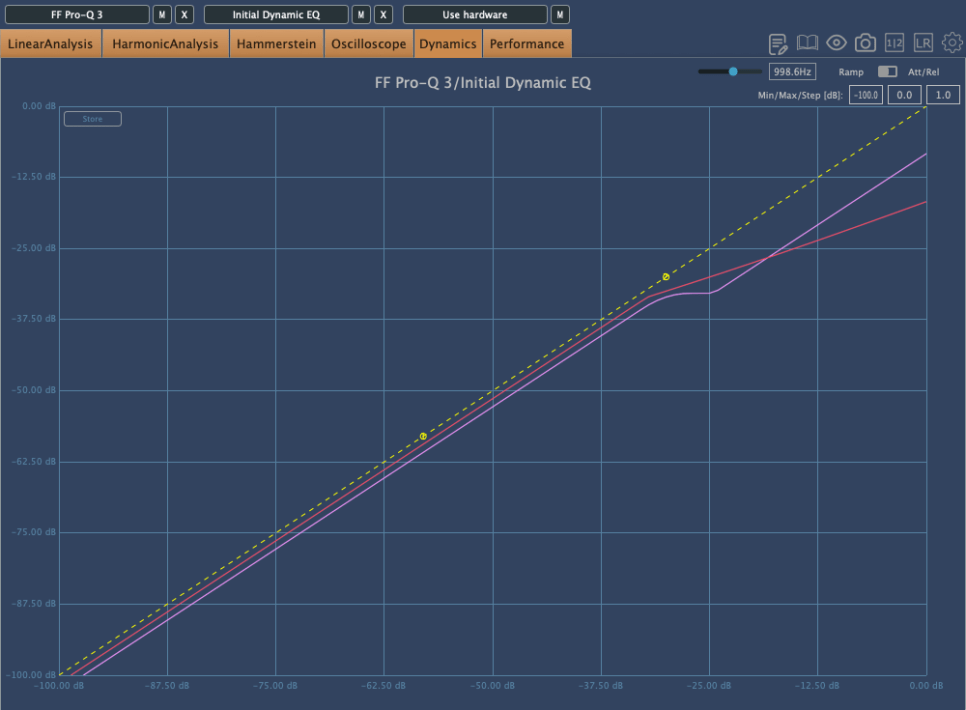

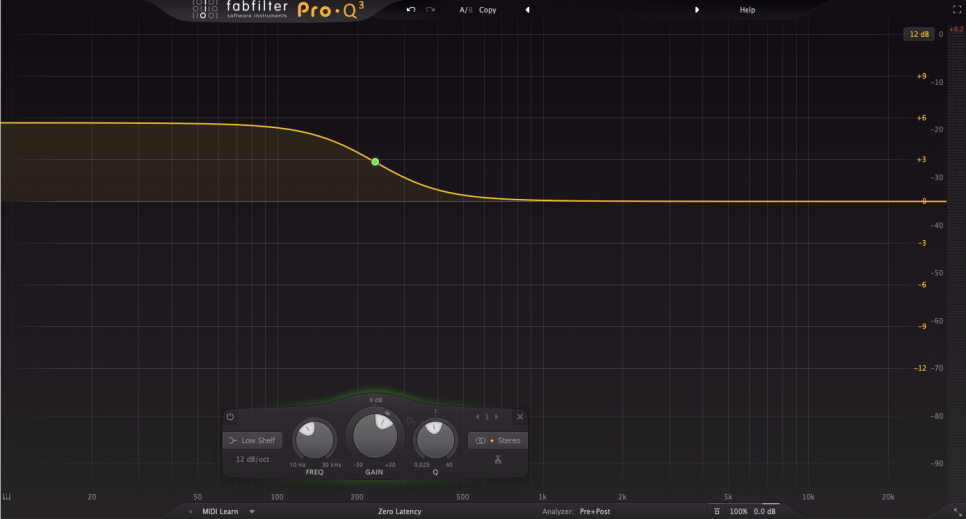

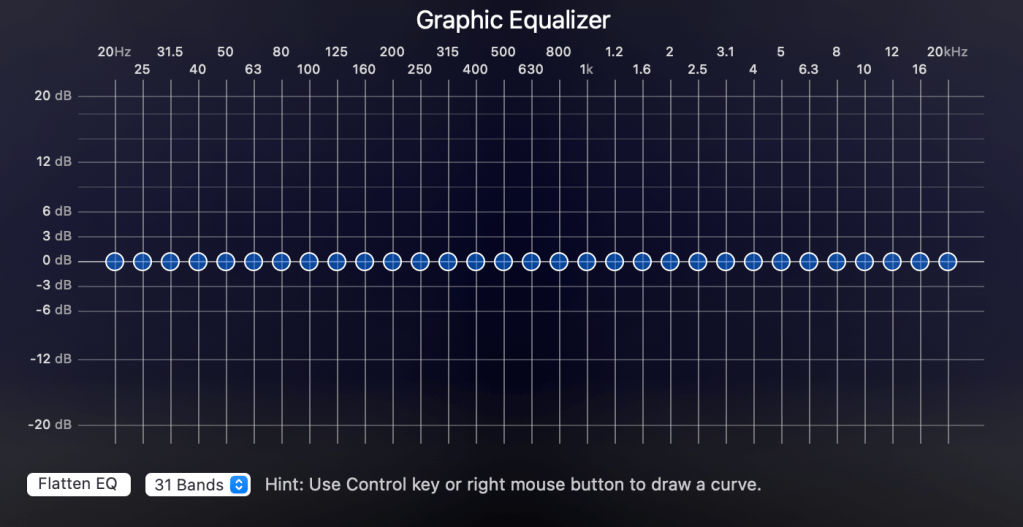

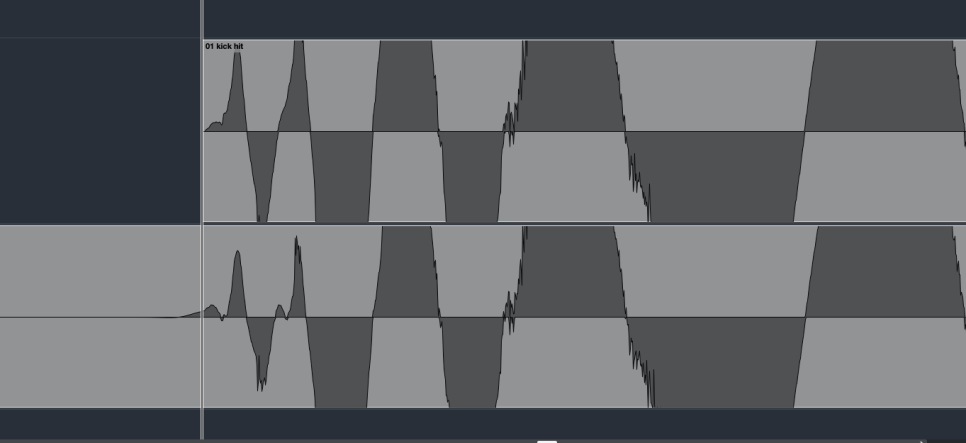

Because of these issues, Linear Phase EQ was developed. Linear Phase EQ does not cause phase issues. However, it introduces a phenomenon known as Pre-Ringing.

- Pre-Ringing Phenomenon

Pre-Ringing occurs when using Linear Phase EQ, causing the sound to ring before the waveform. Try bouncing your track using Linear Phase EQ. As shown in the image above, you’ll notice a waveform appearing at the front that wasn’t there originally.

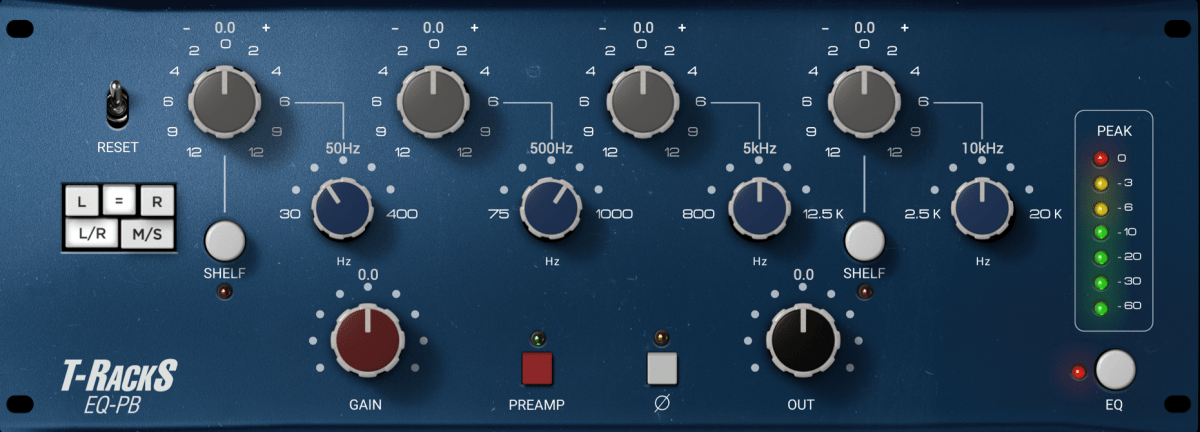

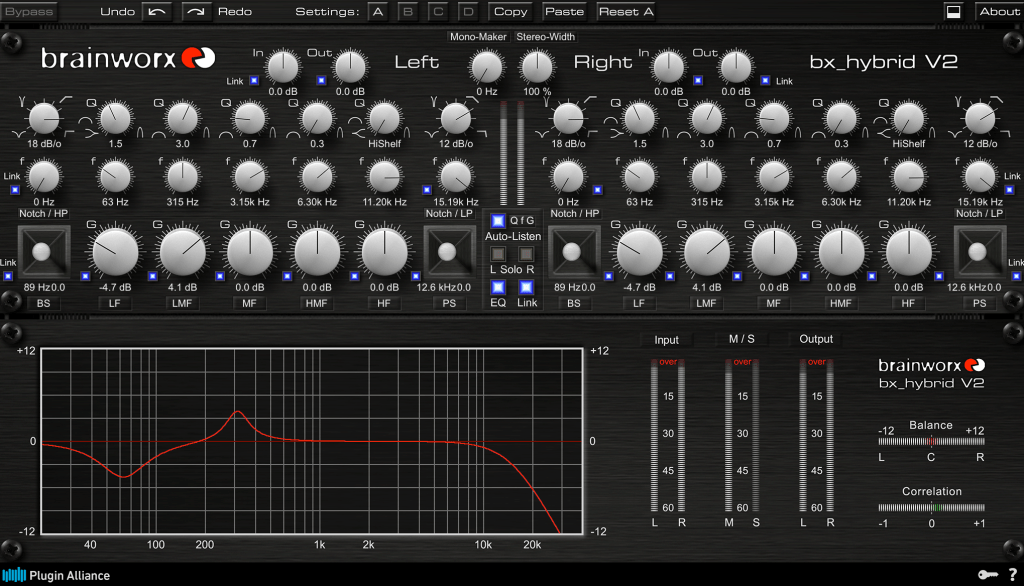

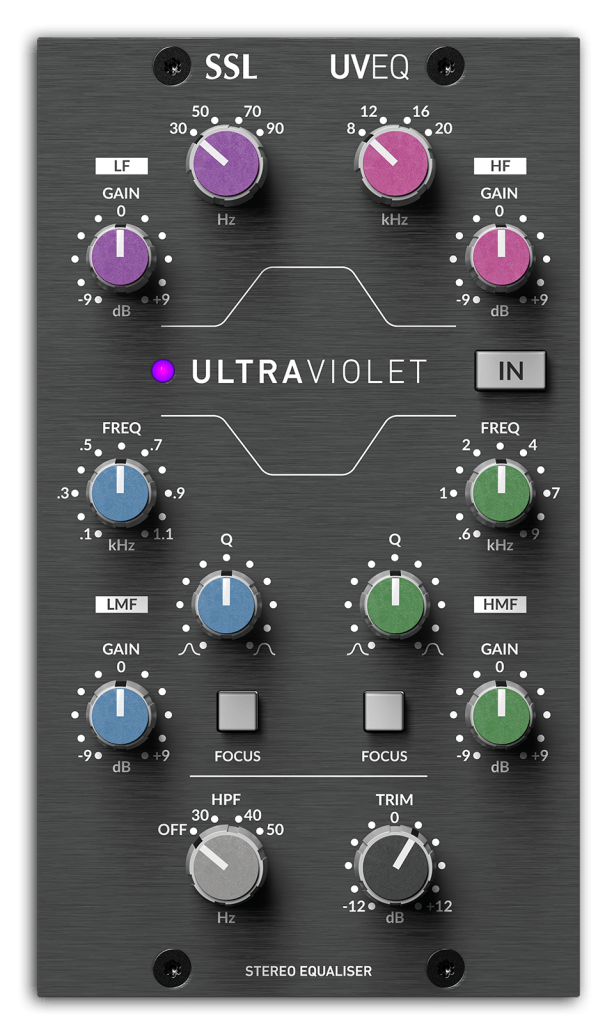

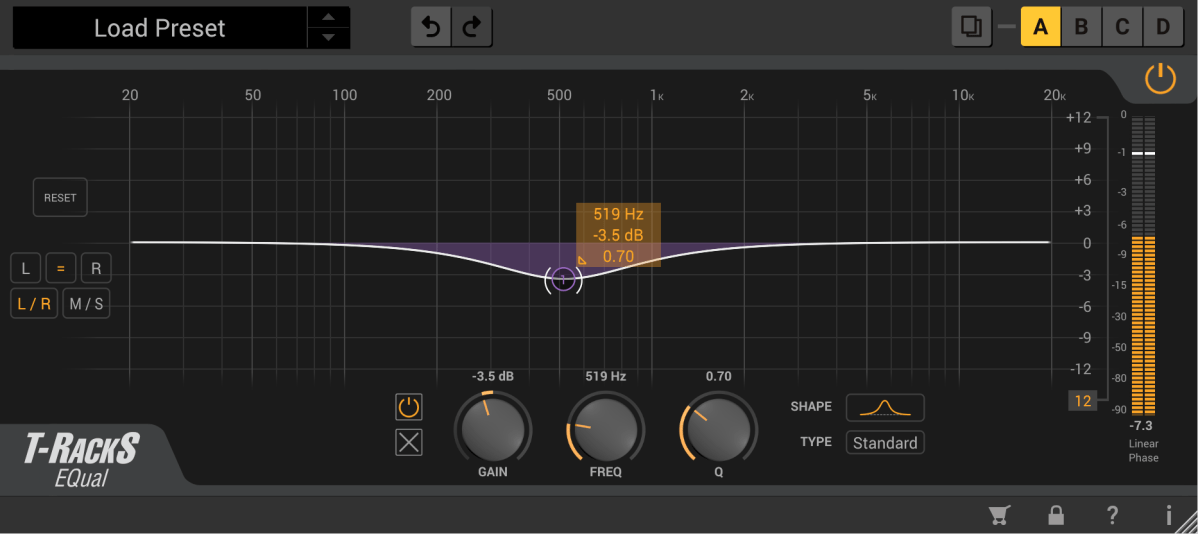

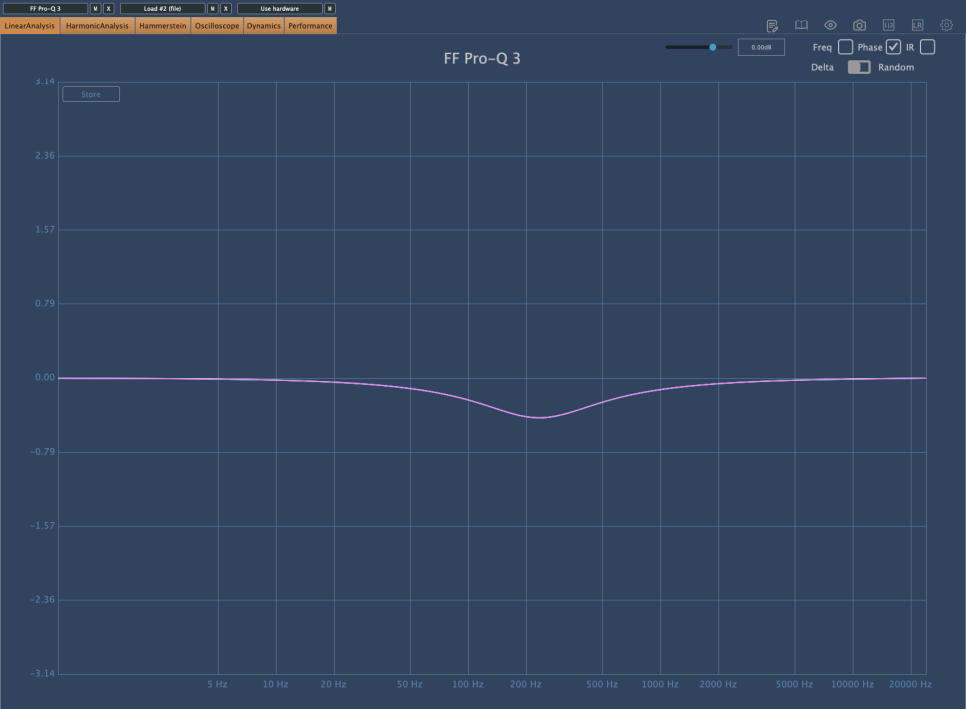

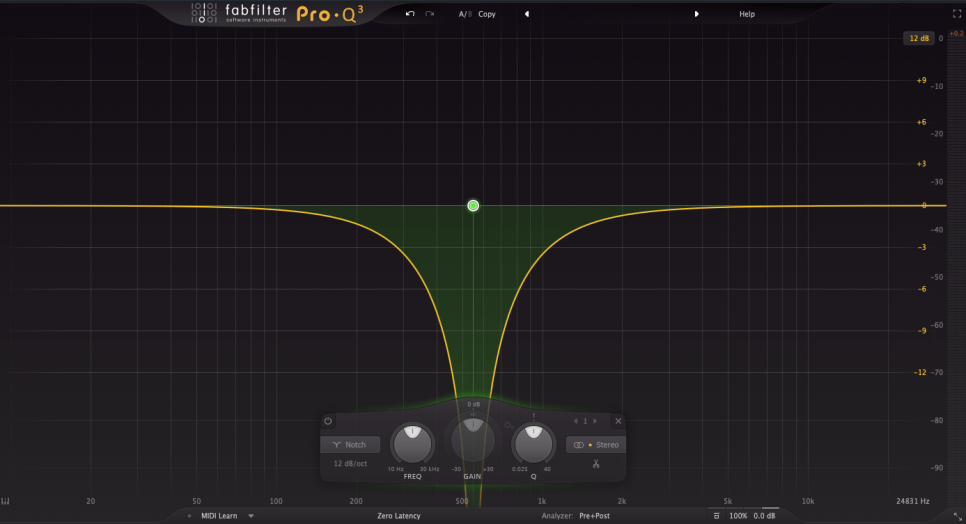

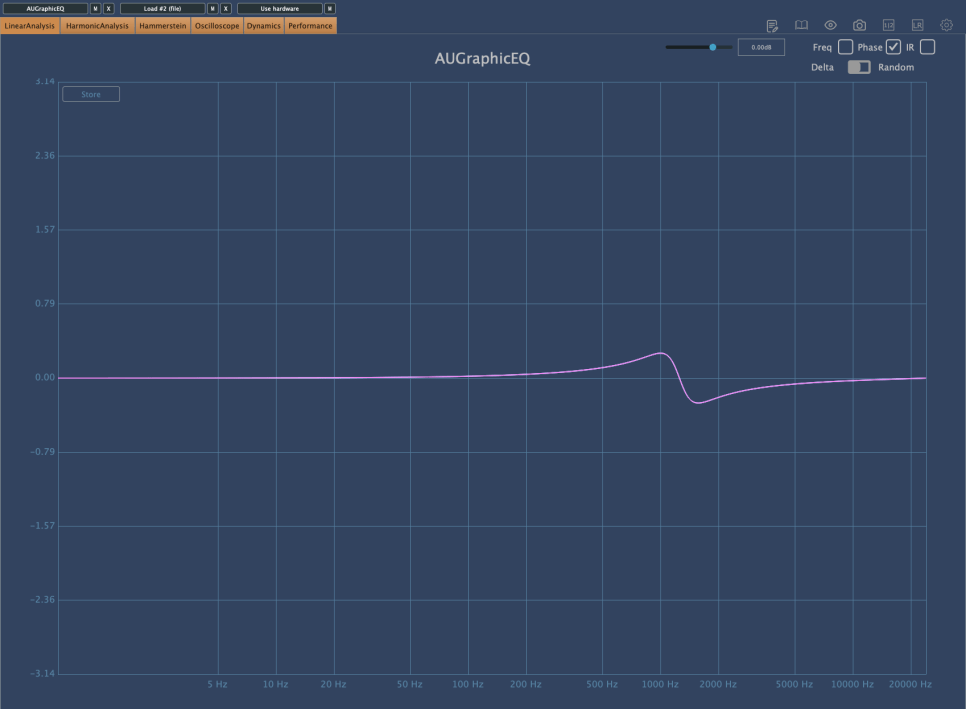

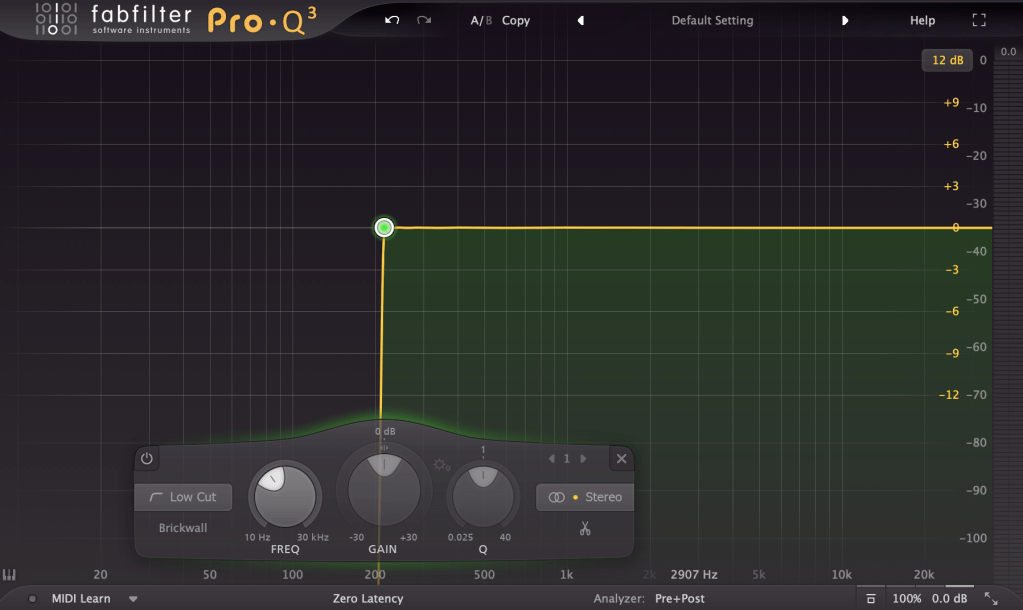

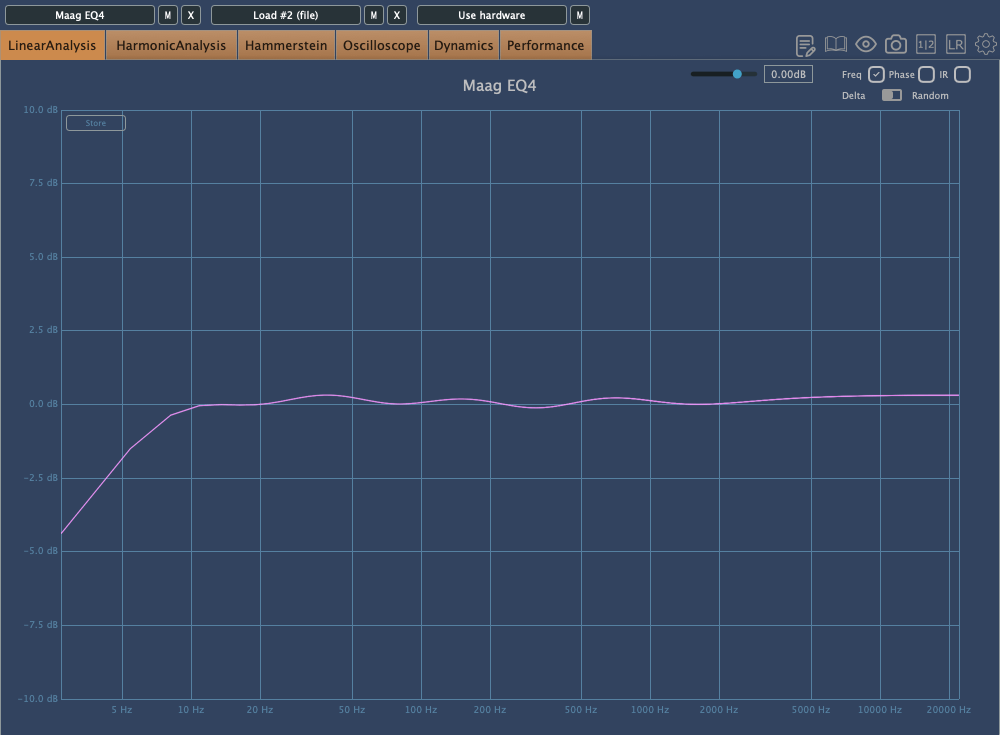

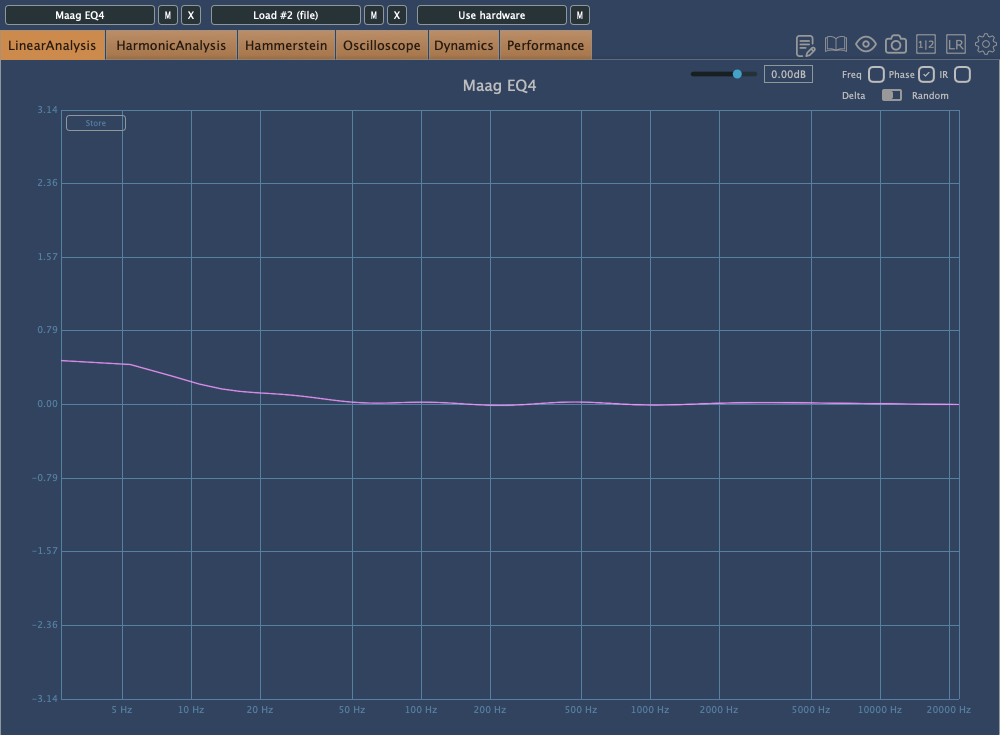

Other than digital EQs, many plugin emulations of analog EQs alter the phase and frequency response graphs just by being applied.

For instance, consider the commonly used Maag EQ4 for boosting high frequencies.

On the left is the frequency response graph when only the Maag EQ4 plugin is applied without any adjustments, and on the right is the phase change graph under the same conditions.

Here’s what we can deduce about using EQ:

- Applying an EQ can change the basic frequency response from the start.

- Non-Linear Phase EQs will inevitably cause phase changes.

- Linear Phase EQs can introduce Pre-Ringing, creating new sounds that were not there originally.

- EQ plugins or hardware with Harmonic Distortion can add extra saturation to the sound.

Understanding these points is crucial when adjusting EQ.

Of course, there are many excellent engineers who achieve great results without knowing all these details. Ultimately, the most important thing is that the sound comes out well, regardless of understanding the underlying principles.

However, I personally feel more comfortable when I have a solid understanding of the fundamentals. So, knowing this information can never hurt.

That’s all for today. I’ll see you in the next post!