Hello! This is Jooyoung Kim, a mixing engineer and music producer.

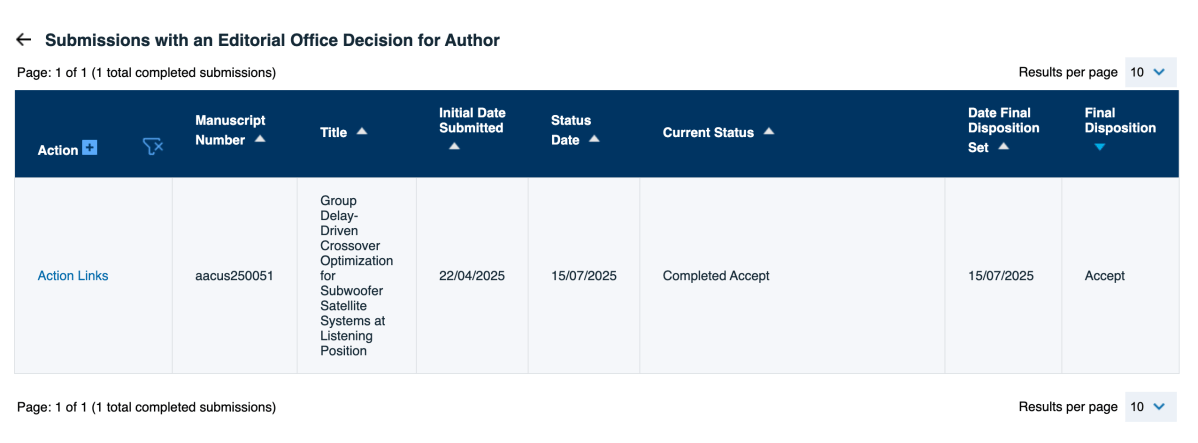

I’ve finally completed my personal challenge: getting a SCIE-level paper accepted before earning my master’s degree. Despite several rejections, it took me five and a half months to receive acceptance.

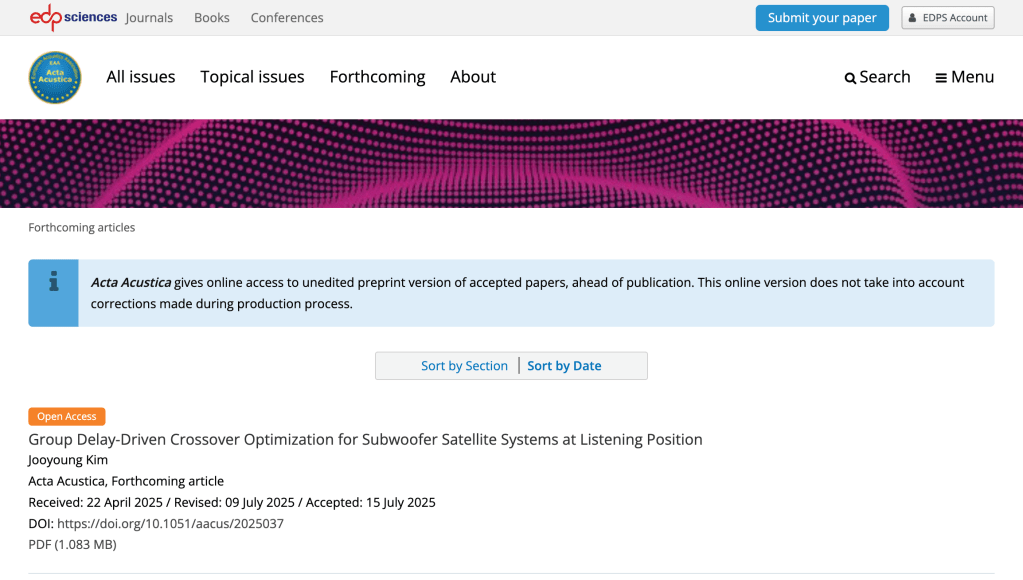

The paper has been accepted by Acta Acustica, a journal published by the European Acoustics Association (EAA), though it’s not officially published yet.

However you can see the prototype of the paper at “Forthcoming” page.

So, Acta Acustica, published out of France, feels like a journal with some solid history and tradition. But, maybe because it’s changed names a few times, it seems to have slipped a bit in the journal rankings.

Honestly, when it comes to music and acoustics journals, Impact Factor (IF) is practically useless for judging quality. It’s like they’re in their own little world! The top dogs, like the journals from the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) and the Audio Engineering Society (AES), are ranked Q2 and Q3 in JCR’s Acoustics category. Q3 for AES? That’s just absurd, right? 😅

Anyway, Acta Acustica is a notch below those two, sitting at Q3. Still, for music and acoustics research, there aren’t many other suitable journals out there besides these three. I was genuinely worried about getting rejected, so making it through feels like a huge relief.

Oh, and get this—acceptance doesn’t mean it’s published right away. There’s this final polishing phase handled elsewhere, and when I looked over my manuscript again, I spotted some typos… I’m planning to fix everything before submitting the final version.

Also, you might’ve noticed from the author list—I wrote this paper as the sole author! It’s on the same topic as my master’s thesis, but I did everything on my own: no funding whatsoever, not even for the research itself. I used three subwoofers for the experiments—two were mine, and just one was borrowed from my professor’s personal stash. Even the measurement microphone was my own. I designed all the research methods from scratch, and I figured I should be the one handling revisions and post-publication queries as the corresponding author. I talked it over with my professor, who was super kindly lent me that one subwoofer. Huge thanks to him! 😄

The journey wasn’t easy—two rejections and some brutal feedback later, I had to tweak a lot of the research methods compared to my thesis. The conclusion ended up similar, but the paper itself feels like a different beast now.

Oh, and here’s the kicker: I had no money, and my university doesn’t cover publication fees or open access costs, so I was stressing out big time. But then, Acta Acustica turned out to be a Diamond Open Access journal—free for everyone to read and free for authors to publish!

I actually tried building an application based on this current work using Python, but there were way too many features to cram in, so I’ve put it on hold for now… haha.

And also I’m already thinking about my next research topic, and if it goes as planned, I might even turn it into a plugin.

Looking at how I barely touch social media like Instagram and stick to blogging, I guess writing’s just my thing. So, until my next post—catch you later!