Hello everyone, this is mixing engineer and music producer Jooyoung Kim.

It’s been another busy week, so this one’s going to be a short life update post. ^^;

Last Saturday, we held the second “Frisketch x Yeonjun Yoon | Um” concert.

I worked as the sound director again. We used the same venue as the June concert, but this time we positioned the piano differently.

In the meantime, I picked up another Peluso P87 and added two RØDE NT55s for ambience. The sound came out much closer to what I had in mind this time.

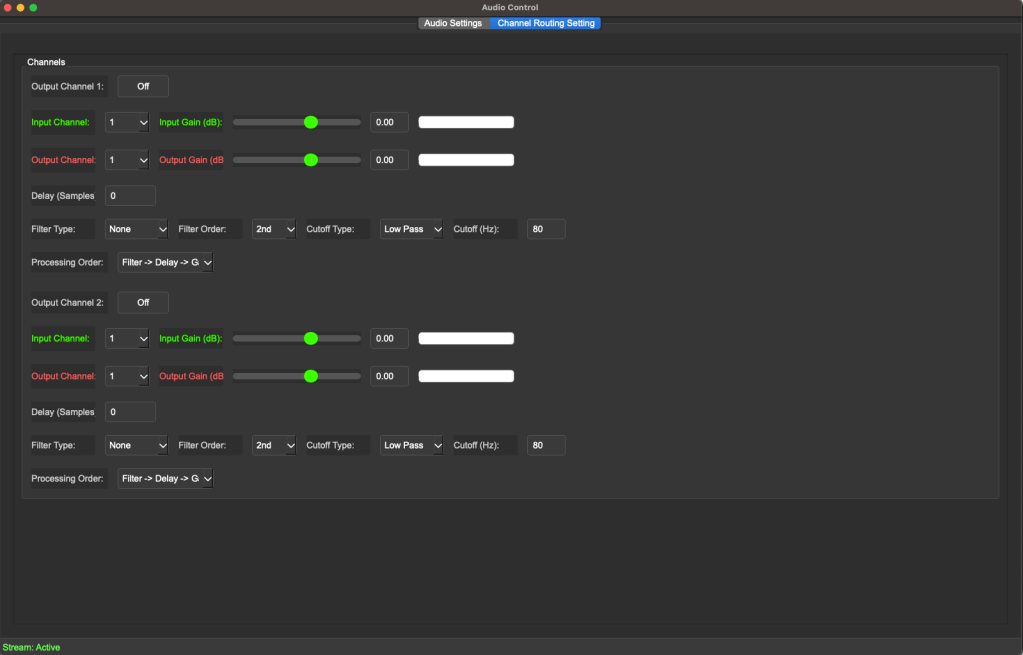

Because of the speaker placement, I decided to run the mix in mono. Since the only instrument was the piano, the main mic (P87) captured it beautifully.

That said, when the artist mentioned, “I wish the piano tone were a bit less metallic,” I completely agreed. Haha.

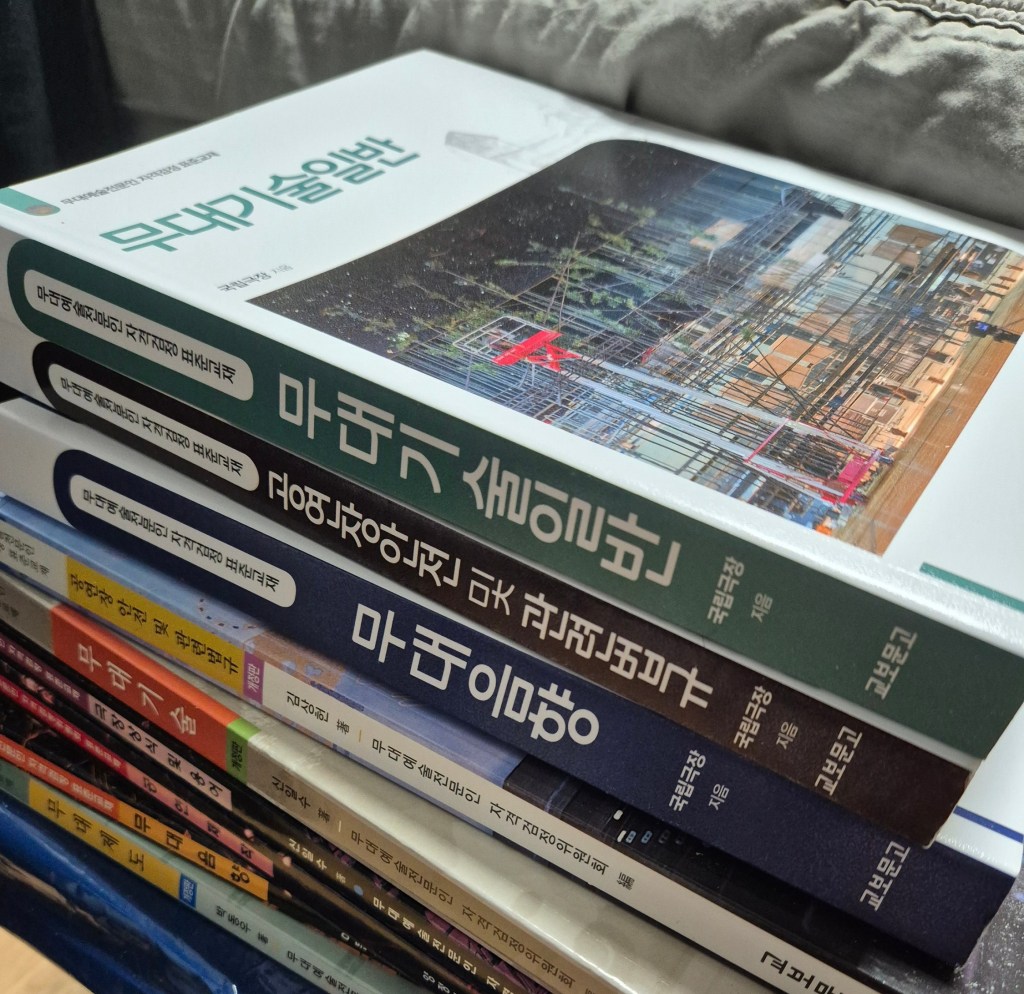

Then on Tuesday and Wednesday, I assisted Sound Director Sung-won Yang in his class “Mixing with IR Reverb” at the Arko Arts Human Resources Institute in Ilsan.

On Wednesday afternoon, I took over and led the mixing lecture myself.

Sometimes I wonder if I made things too difficult, but the topics I consider most important in mixing tend to be the challenging ones.

So I told the students, “It’ll all make sense later—trust me,” and just went for it. Haha.

Honestly, I had so much I wanted to cover, but time was short. I trimmed and trimmed until the lecture fit the schedule perfectly—but it still felt a bit like a Spartan session.

Hopefully it wasn’t too much to absorb all at once.

By the way, I don’t think I’ve mentioned this here before, but I’ve been teaching major practical courses at my graduate school since finishing my master’s degree.

I used to give private lessons only to a few close acquaintances, but now that I’m officially teaching as part of the program, I’ve been thinking a lot more seriously about pedagogy and teaching methods.

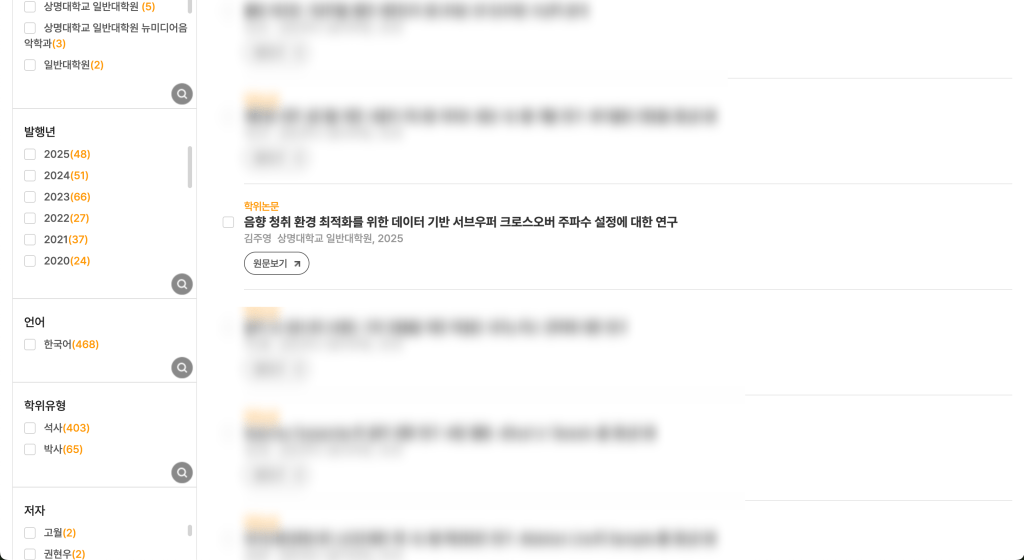

Also, my master’s thesis has finally appeared on D-Collection (The archive of theses in South Korea).

The topic is the same as my journal publication, though since it’s an earlier research version, the experimental conditions may feel a bit rougher.

I wanted to cite my published journal paper in the thesis abstract (which is normally standard practice), but unfortunately the publication and submission dates overlapped too closely.

I even contacted the university library afterward, but they said the submission was already finalized and online revisions weren’t possible.

Still, since the journal was published first, there’s no real issue academically.

(For context: a thesis isn’t considered an official publication—once your advisor approves it, the degree is granted.)

Interestingly, I couldn’t find another case online where the timing overlapped this perfectly. ^^;

As for my recent live recordings, I’ve finished most of the mixing, and now my Mac Studio is running endless deep learning sessions again.

Compared to my old Windows PC with a GTX 1080, the Mac runs quieter and stays much cooler.

I’m redoing the experiment I failed back in May, and this time I plan to take my time and turn it into a proper paper.

I already got IRB approval, so I’m hoping the training finishes soon.

(Each CNN run takes about 20 days, by the way… hahaha… ha… 😭)

I’m planning to try a WaveNet model as well, but I’m slightly worried it might overrun the IRB deadline. 😭

That’s how things have been lately.

See you in the next post!