Hello, this is Jooyoung Kim, an engineer and music producer.

Previously, I mentioned that I had to custom order and repair a toroidal transformer for my Stam Audio SA-2A. After it was fixed and returned, I was quite satisfied. However, I realized I needed more rack space, so I decided to buy a new rack cabinet.

Thinking ahead about the additional equipment I’d be adding, I also bought a patch bay and cable connectors.

I wanted to get a Samson patch bay to match my other gear, but since there were no Samson S-Patch bays available for delivery to Korea on Amazon, I ended up buying the cheapest one that could be set to Normal mode.

The yen was quite weak recently, so I took advantage of that when purchasing cables and connectors via Rakuten. I bought 100 meters of Canare L-2T2S cable and around 20 Neutrik TRS and XLR connectors.

After looking around, I decided to order a custom-made rack cabinet from Shinsun Workshop(Korean: 신선공방), as their products seemed the most suitable. Other ready-made options were either too shallow or too deep for my setup.

I pre-made the cables and installed everything.

Haha… It was quite a task. I started around 4 PM and finished by 11 PM, with breaks for meals. I even had to do some soldering because I forgot something with the multi-cable… haha…

But in the end, everything looked neat and tidy. I forgot to take a photo of the finished setup, though. After repeatedly sitting and standing, my legs were shaking the next day.

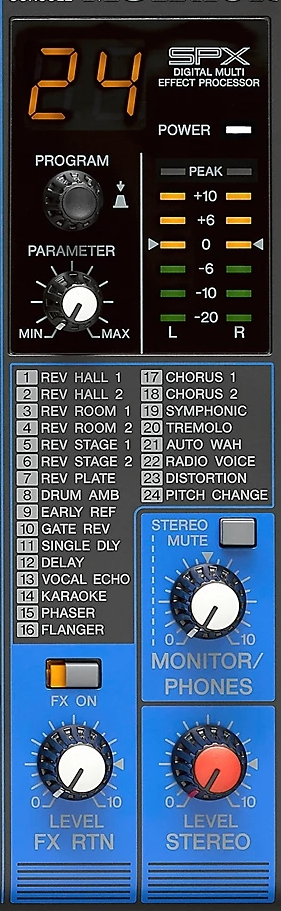

I plan to add a 2U tube preamp to the large rack cabinet, and a Behringer 369 to the smaller one. That will leave about 1U of space, which I might use for an API 2500 or a saturator later on.

I recall making a resolution last year not to buy any more equipment, but I’ve completely broken that promise. Despite buying things relatively cheaply, I should be spending money on releasing my songs. It’s quite ironic that I’m spending all my song budget on gear… Equipment addiction is real…

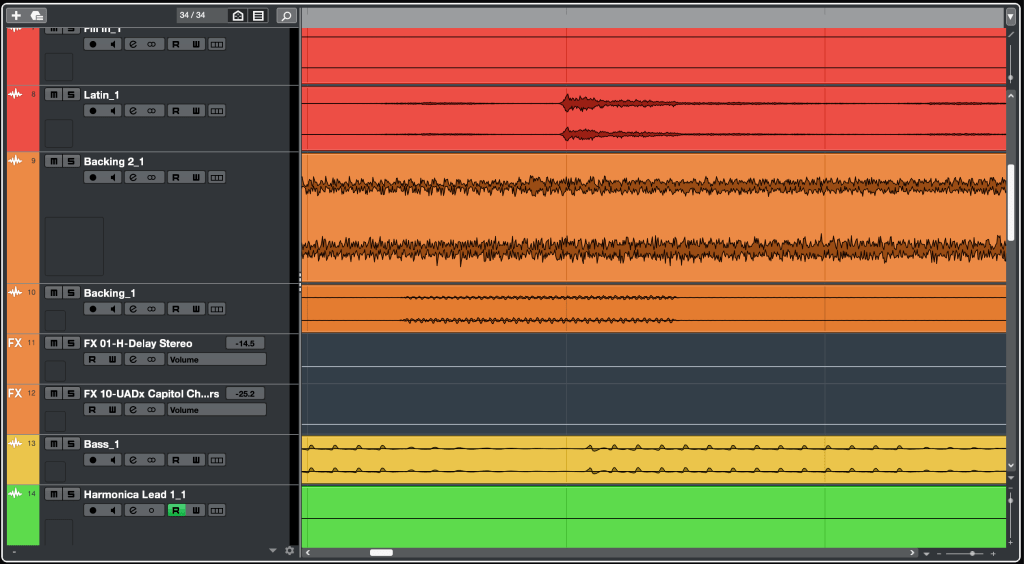

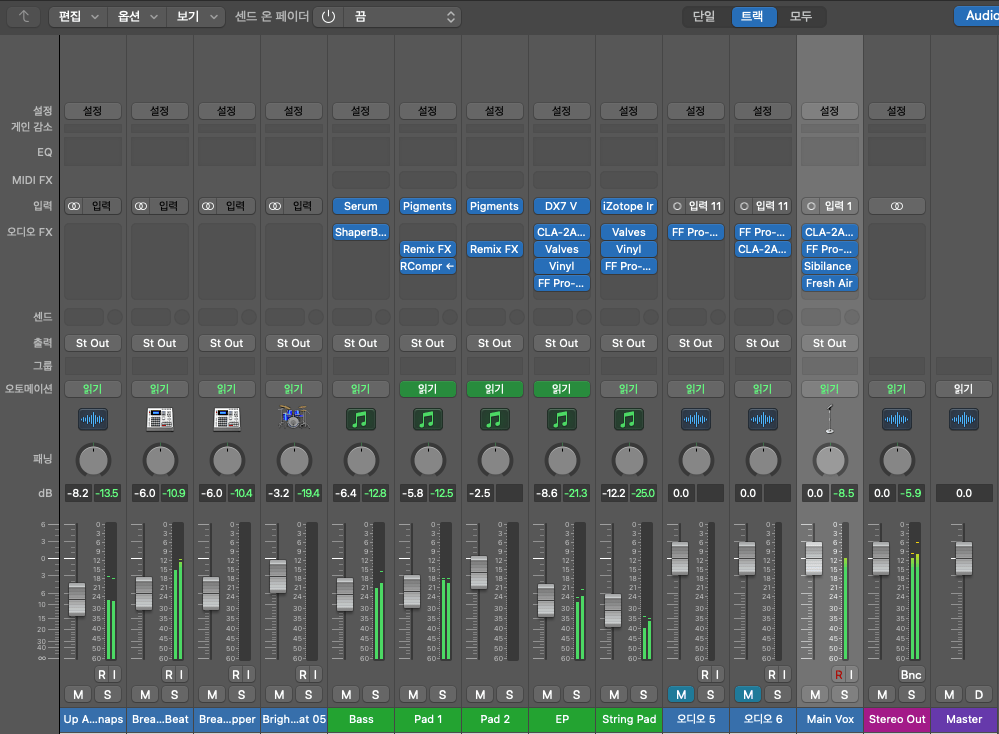

Lately, I’ve been collaborating with a contact I met through a previous project. We’re producing a few tracks together. Additionally, I’ll be recording and mixing a song for a regular client.

I haven’t posted much about my recent work or projects, but these collaborations have been fun, and I plan to share more once they’re finished.

See you in the next post! 🙂