Hello! I’m Jooyoung Kim, a mixing engineer and music producer.

Today, let’s talk about volume and signal levels.

If you’re interested in sound, you’ve likely heard the term “Equal Loudness Contour.”

This term refers to the fact that our ears perceive different frequencies at different volumes. The curves that connect sounds perceived as being of equal loudness are known as equal loudness contours.

Looking at the graph, you can see that humans tend to hear less of the low and ultra-high frequencies and more of the high frequencies at the same volume level.

(*Recently, the standard for Equal Loudness Contour was revised from ISO 226:2003 to ISO 226:2023.)

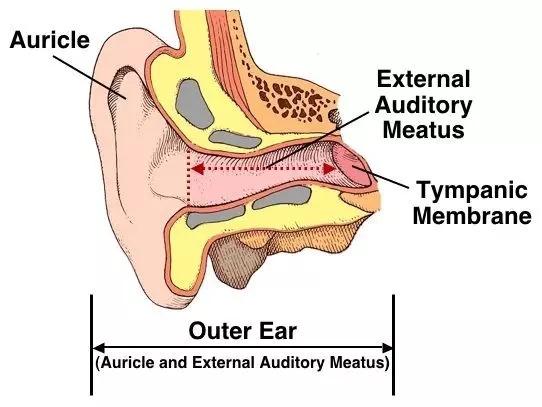

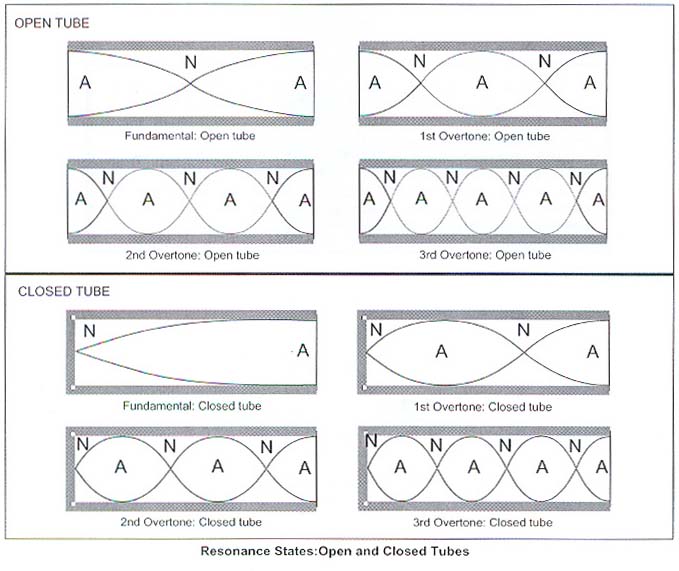

This phenomenon occurs because our ears are shaped like a closed tube.

A closed tube resonates at wavelengths that are at least one-fourth the length of the tube. The external auditory meatus (ear canal) is typically about 2.5 cm long, so it can resonate with sound waves that are around 10 cm in wavelength.

Since the speed of sound is typically calculated at 340 m/s, we can determine that the resonant frequency is approximately 1700 Hz. Additionally, the resonances in the ossicles make the high frequencies more audible.

Why is this important to know?

The equal loudness contours show that as volume increases, the lows and highs sound more balanced. This is why music mixed at high sound pressure levels (SPL) can sound tinny or weak when played at lower volumes.

So, what is an appropriate volume level for mixing? Generally, 80 dB SPL is used as a standard. Famous mastering engineer Bob Katz recommends using 83 dB SPL.

(Here, dB SPL refers to the decibel unit used to express sound levels, such as airplane noise or inter-floor noise.)

I found a video from Presonus that discusses how to set speaker volume. For those who work in home studios, 80 dB SPL might sound quite loud. Personally, I work around 75-70 dB SPL as 80 dB can be painful for my ears. Just make sure you’re not working with the volume too low.

Now, let’s move on to basic signal levels.

In audio, there are four main types of levels:

1) Microphone Level / Instrument Level

- These signals are very weak and need to be boosted to line level using a microphone preamp or DI box.

2) Line Level

- This is the level at which audio equipment typically communicates. It’s used in audio interfaces, mixers, hardware EQs, compressors, and other devices.

3) Speaker Level

- To play the signal through speakers, it needs to be amplified to speaker level. This requires a power amplifier. Active speakers have built-in power amplifiers, whereas passive speakers need an external power amplifier.

4) Mixing Level

- The levels dealt with during mixing are almost all line levels.

Line level is usually divided into two categories: Pro Line Level and Consumer Line Level. Pro Line Level is based on +4 dBu, while Consumer Line Level is based on -10 dBV.

- dBu is a unit based on 0.775 Vrms.

- dBV is a unit based on 1 Vrms.

(Brief Explanation of RMS : Since electrical signals are AC, simply averaging them would yield a value of zero. Therefore, the root mean square (RMS) is used to find the average.)

When converting between these units, nominal level and peak level differ. Pro levels are higher, and consumer equipment typically has lower headroom, which can cause compatibility issues with pro equipment.

However, modern high-fidelity equipment often has high signal levels, so it’s becoming less of a concern.

That’s about all you need to know about signal levels.

With this foundational knowledge, we’ve covered the basics needed for mixing. In the next article, we’ll look at DAW functions in detail.

See you in the next post!