Hey there! I’m Jooyoung Kim, a mixing engineer and music producer.

Ugh… English has been killing me lately. Seriously… 😭

I wish it would just sink into my brain step by step, but it feels like I’m cramming it in, and my head’s about to explode. Words, especially, are the worst. Haha.

Anyway, with my schedule being so tight, I’m finally getting around to writing this on the weekend.

It’s been a while, but I’m back with another post on synthesizer basics! 😊

Today, we’re diving into vector synthesis and wavetable synthesis.

Ready? Let’s get started!

(By the way, if you make a purchase through the links in this post, I may earn a small commission, which helps me keep the lights on and keep creating content!)

Vector Synthesis

Vector synthesis was a fresh concept introduced by Sequential in the 1980s with their Prophet VS synthesizer.

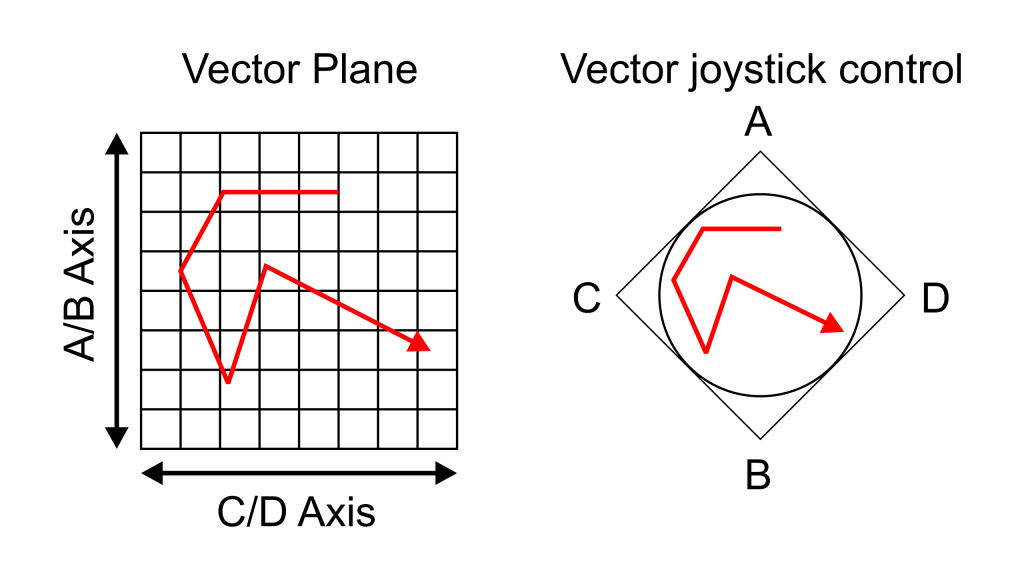

This method assigns different sound timbres to the four corners of a square. Using a joystick, you can intuitively blend these sounds together! The resulting sound, created by mixing these four sources, can be represented as a single point on a coordinate plane using vectors—hence the name “vector synthesis.”

(If you took physics as an elective in high school, this concept might feel pretty familiar!)

Later, Sequential was acquired by Yamaha, and the development team moved on to join Korg. This led to the release of two vector synthesizers: the Yamaha SY22 and the Korg Wavestation.

Arturia has a virtual instrument called Prophet-VS V.

Korg also released a virtual version of the Wavestation, bringing its advanced vector synthesis system to software.

If you’re curious about vector synthesizers, these are worth checking out!

Wavetable Synthesis

Wavetable synthesis actually predates vector synthesis by a bit. It was first utilized in MUSIC-II, a sound design program developed by Max Vernon Mathews in 1958. It was later commercialized by PPG with their Wavecomputer 360 in the late 1970s and the Wave series in the 1980s.

The concept? It’s about mixing different waveforms to create new sounds. It’s somewhat similar to vector synthesis, in that both methods interpolate between different timbres to generate a sound. That’s why I’m covering both in the same post! 😄

The key difference is this:

- Vector synthesis calculates the volume balance between four sound sources based on their position in a coordinate plane.

- Wavetable synthesis works within a single waveform cycle, calculating the amplitude ratios of different waveforms.

This distinction should help clarify how the two approaches differ.

Also, you might notice that both vector and wavetable synthesizers let you tweak the ADSR (Attack, Decay, Sustain, Release) parameters independently. If you’ve read my earlier post on subtractive synthesis, you’ll know I mentioned that these parameters are pretty universal across synthesis methods.

If you’re feeling a bit lost, check out that post for a primer on using something like a Minimoog. Most synths don’t stray too far from that foundation, and trust me, you’ll end up using a Minimoog sound in a track at least once in your life! 😄

Waldorf has recreated the PPG Wave as a virtual instrument, bringing back its iconic 80s sound.

There are tons of wavetable synths out there—Serum, Waves, the free Vital, and LANDR Synth X, to name a few. My personal recommendation? Go with Serum. It’s got a huge user base, which means tons of presets and a great community. Plus, it’s just well-designed.

A Few Final Thoughts

The thing about vector and wavetable synthesis is that you can’t pin down their sound to something specific like sine, triangle, square, or saw waves. Throw in a bunch of different sounds, and the output changes dramatically. Unlike FM synthesis or analog subtractive synthesis, it’s hard to describe the “typical” sound of these methods. 😅

Personally, I love messing around with synthesizers to craft the perfect sound, but it can be a time sink. My advice? Start with a preset that’s close to what you’re after. (If you familiarize yourself with basic waveforms like sine, saw, triangle, and square, it’ll be easier to figure out which category your desired sound falls into.) Build your track first, then tweak the sound later to get it just right.

That’s it for today! Thanks for reading, and I’ll catch you in the next post! 😊