Hey there! I’m Jooyoung Kim, a mixing engineer and music producer.

Lately, I’ve been drowning in code.

The program I mentioned in my last update? Yeah, I totally messed up the THD measurement part by mixing it up with the standard crosstalk measurement method. So, I had to scrap everything, re-measure the data, and start over. It’s been taking way longer than expected, and I’m exhausted, haha.

Because of this, my blog posts have been delayed quite a bit.

Thankfully, I wrapped up the measurements this morning, so now I can just tinker with the program whenever I have some spare time.

Anyway, today I want to dive into additive synthesis, continuing our series on synthesizer basics after covering subtractive synthesis last time.

Just a heads-up: the virtual instrument links I recommend throughout this post are affiliated with Plugin Boutique. If you purchase through those links, I earn a small commission, which really helps me keep the lights on. Thanks for the support! 🙂

Let’s get started!

Additive synthesis, as the name suggests, is all about combining sounds to create something new.

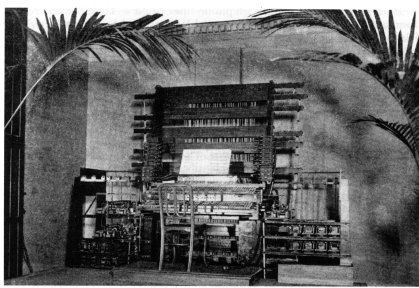

The earliest instruments to use this method were the Telharmonium and the Hammond Organ.

These instruments had built-in tone generators called tone wheels, designed to produce specific sounds when you pressed a key.

If you’ve ever seen a Hammond Organ, you’ve probably noticed its drawbars. These let you control how loud or soft the fundamental tone and its harmonics are played. By adjusting them, you could mix the sounds from multiple tone wheels to create a wide range of timbres.

In a way, you could call the Hammond Organ an early mechanical analog synthesizer based on additive synthesis. That said, it’s a bit different from the subtractive synthesis we typically talk about today, right?

When it comes to virtual Hammond Organ plugins, I think IK Multimedia’s Hammond B-3X and Arturia’s B-3 V are the top dogs.

During this summer sale, IK Multimedia’s Total VI MAX bundle, which includes Hammond B-3X, is an absolute steal. Honestly, if you’re thinking about getting just the Hammond B-3X, you might as well grab the whole bundle—it’s super versatile and worth it.

Now, let’s get a bit technical for a moment.

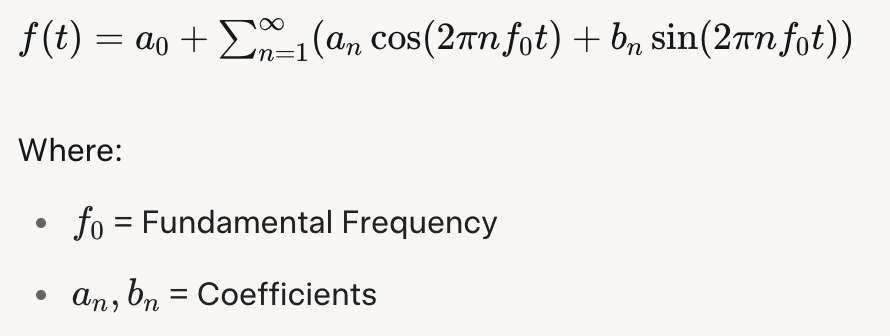

According to the Fourier Series, any periodic signal (like a sound wave) can be expressed as a sum of sine waves:

The Fourier Transform takes this further, allowing even non-periodic signals to be represented as a sum of sine waves:

In theory, this means you can recreate any sound just by combining sine waves.

Sounds like a ton of manual work, right?

Back in the day, not only were these calculations a nightmare, but even playing multiple sounds simultaneously through sampling was a challenge for early computers. That’s why additive synthesis evolved alongside advancements in computing power.

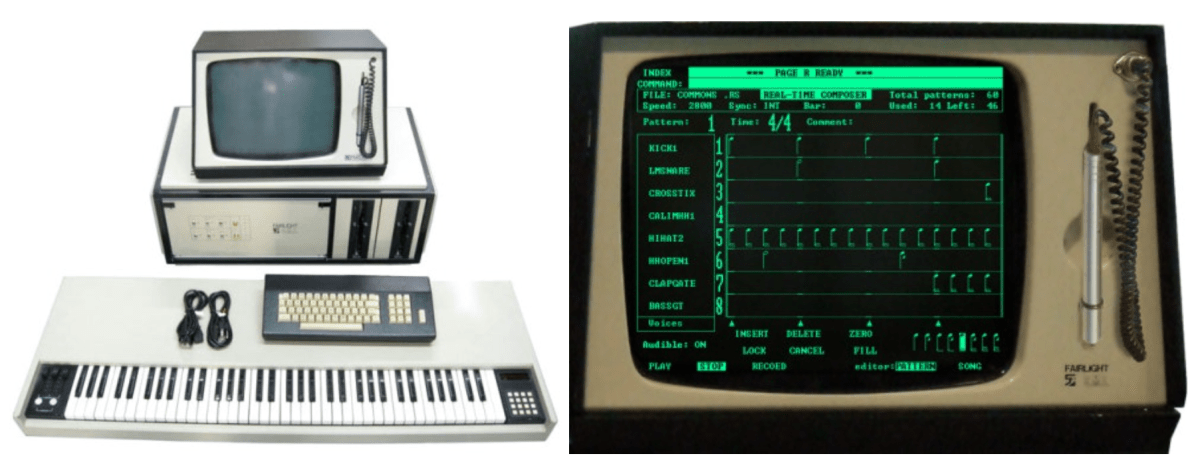

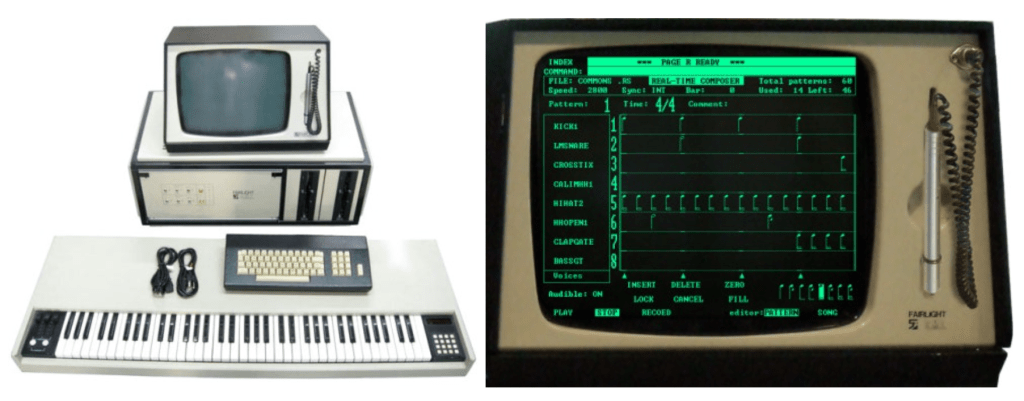

A standout product from this transitional period is the Fairlight CMI.

This beast wasn’t just an additive synthesis synthesizer—it was also a DAW and a sampler.

The panel on the right in the photo is the DAW interface, complete with a stylus for tapping out rhythms on the screen. Pretty cool, right?

One of the Fairlight CMI’s built-in samples, called Orchestra Hit, became iconic in pop and hip-hop. It’s a short orchestral tutti sound from Stravinsky’s The Firebird. Using it in a track instantly gives off that classic 80s–90s old-school vibe.

Arturia’s CMI V plugin does an incredible job of recreating the Fairlight CMI’s interface, complete with its early DAW and mixer windows. It’s a lot of fun to play around with!

Another notable instrument from this era is New England Digital’s Synclavier, which combined FM synthesis and additive synthesis while also functioning as a DAW and sampler. Originally licensed by Yamaha for FM synthesis, by version II, it basically became a full-fledged computer, haha.

Arturia’s got a plugin for this one too. They’re really out here trying to recreate every classic synthesizer as a plugin, aren’t they?

You might’ve noticed by now that additive synthesis is deeply tied to samplers and DAWs. After all, when you layer different sounds at the same time in a modern DAW, you’re essentially using it as a sampler and an additive synthesis synthesizer.

As technology progressed, synthesizers started incorporating wavetable synthesis, allowing for even more precise and varied sound design.

Explaining how to use a specific additive synthesis synthesizer is a bit tricky because it’s really just about layering sounds, using samplers, and working in a DAW. So, I hope this brief history gives you a good sense of it!

That’s all for now—see you in the next post!